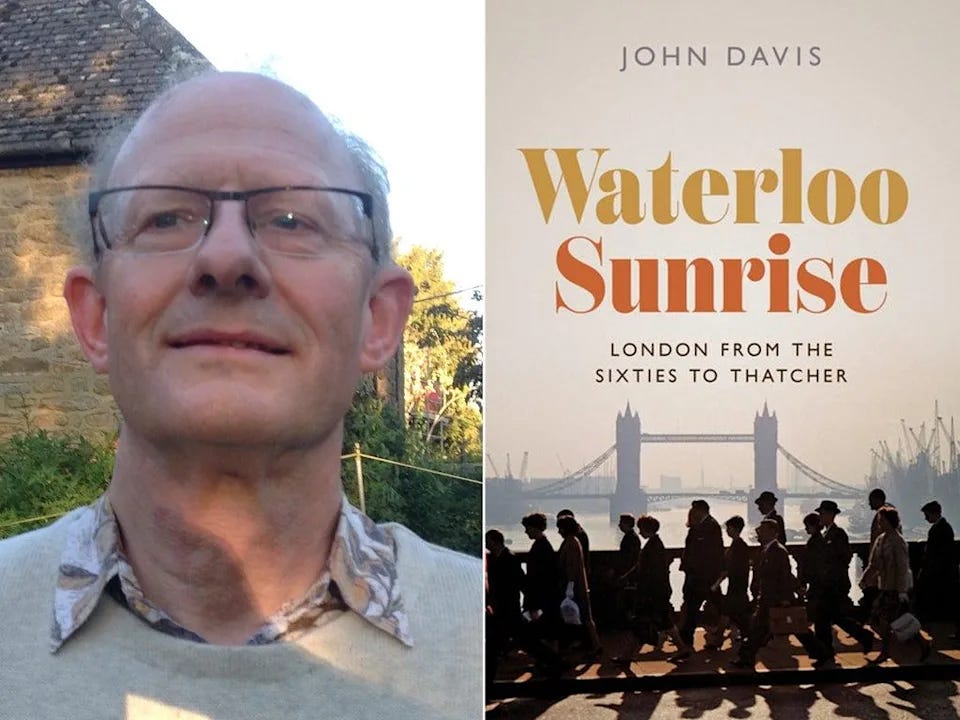

An interview with historian and author, John Davis

The author of 'Waterloo Sunrise' on smelly rivers, swinging Sixties and London on the skids

As well as being emeritus fellow in history at Queen’s College Oxford, John Davis has spent the last twenty years researching and writing Waterloo Sunrise: London from the Sixties to Thatcher, which the blurb describes “a kaleidoscopic history of how the 1960s and 1970s changed London forever.”

It’s an incredible book, insanely detailed with an almost fanatical amount of research evident in every page. But if that makes it sound dry and academic then we’re not doing it justice. All that research means Davis is able to bring the London of half a century ago to life in a very vivid way as he covers topics like 60s fashion, Soho’s sex trade, restaurants, nightlife, cabbies, gentrification and suburbia.

We spoke to John last month, just after the publication of the book, to ask him about what motivated him to take on such an enormous task, if ‘Austin Powers’ is an entirely accurate representation of ‘swinging London’, and what the history of the city might be able to tell us about its future.

Hi John. The question we try and ask everyone we speak to is: how would you describe your connection to London? I think I’m right in saying you were born here?

That’s right. I was born in Lewisham in 1955. So the period I’m writing about in the book, those were the years from my early childhood through to university. I taught at Oxford University until last summer, when I retired. So I now live just outside of Oxford, but I think of myself as being about an hour and a half away from London on a good day.

I read that this book took a long time to write, and you can tell that when you’re reading it. It’s incredibly detailed and it paints a very rich picture of London life during those years. I’m interested in what made you want to take that on. Because it’s not just an academic enterprise is it? It feels like it was quite an emotional undertaking for you.

It is both really emotional and academic. There’s definitely a tug of the heartstrings there, and the thing became a labour of love. I suppose I started working on it, or at least thinking about it, around 20 years ago. The actual writing took less time than that. There are sixteen different chapters in the book, and each of them is independently researched so that ‘labour’ took me a long time, but it’s still one of love.

The book grew out of a paper I used to teach at Oxford in which I focused on the 1960s and 70s in London. The process of teaching that led me to ask questions about how the city changed and why it changed. Like everyone else I was fascinated by and repelled by the whole ‘Swinging London’ thing. I don't deny it existed and I don't want to downplay it, but I think there's a lot more to what London was going through in those two decades than just what was happening in Carnaby Street.

I wanted to ask you about that. Because, obviously the swinging 60s element of London feels like it’s been done to death, but in a very surface level way, a very Austin Powers kind of way: everybody having sex, dancing in the street and having a “groovy time”. It feels to me that you wanted to get under the skin of that time and give it a bit more depth.

Exactly. I’m trying to tread quite a careful line. I don’t want to go down the road of saying “this is all nonsense”, or that it was only enjoyed by about 30 people, because that I think is also wrong. Also, I was born in 1955, so I wasn’t old enough to be swinging in 1966! But I can just about remember that something was changing in a city that was still bomb damaged and had a smelly river. That’s something that will strike a chord with anyone of my age: that the Thames used to stink! That was a feature of the industrial city that interwar London had been. When that changes, part of that change is doubtless the ‘Swinging London’ stuff. In the book I call it ‘the swinging moment’.

I think it’s a point at which London is still a vibrant port city, before deindustrialisation really hits in the late 60s. But you’ve also got a rejection of what’s seen as 50s austerity and dullness and greyness. That point at which people are being culturally innovative and imaginative and people still have the money in their pockets to indulge that. But it doesn’t last all that long. By the time you get to the mid-70s, you’ve got London exhibiting a number of the problems that Britain as a whole was suffering from: inflation combined with unemployment and so on.

A lot of people put those divisions that London suffered from at Thatcher’s door. But you paint a more complex picture in this book don’t you? You talk about those things happening a lot earlier and you introduce this idea of London as a kind of anarchic, organic force that can’t be controlled by anyone.

That's right. The book consists of 16, more or less self-contained chapters, which I try to draw together at the end. And the thread that tries to draw them together is that London is anticipating Thatcher’s Britain in all manner of ways, without Thatcher being involved in it more than marginally. So you’re seeing deindustrialisation, but also consumerism which is taking many more durable forms than the more fragile fashion industry of the 60s. I’ve got a whole chapter on how restaurants and eating out changed, for example.

But the overarching theme is that the Britain of the 1980s, both its upsides and its downsides, is very largely anticipated by what’s going on in London in the 1960s and 70s. That’s the process that I’m really trying to look at.

The other big theme in the book is one of redevelopment and destruction. The story of people like ‘demolition king’ Frank Valori and the planners at the Greater London Council who demolished so much of the city in the name of progress.

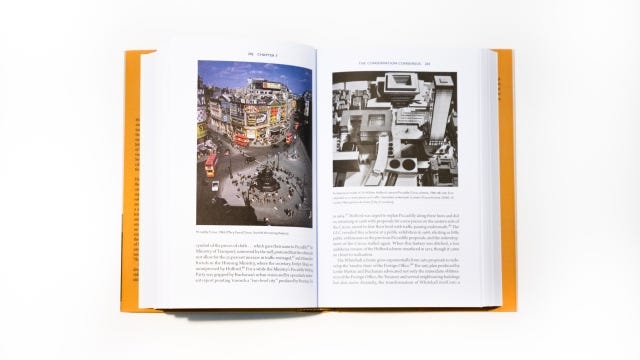

By the time the book ends in the late 70s, a lot of people are saying the familiar line that the planners did more damage to London than the Luftwaffe did. And you can see that a lot of new stuff was thrown up very quickly, although a lot of the plans for major areas like Covent Garden, Whitehall and Piccadilly Circus were so abrasive that they encountered large scale resistance and and weren’t followed through.

I’ve got a chapter on the East End which is largely about redevelopment and the dilemmas it created. Part of the problem being that these areas were in an absolutely wretched condition by the end of the war, and we should never neglect the fact that, whatever you think of high rise residential blocks, the housing that they replaced was really beyond the end of its natural life. But the process of replacing it became so drawn out that the area was a building site for about 20 years, and living in a building site for 20 years is not much fun. It turned out to be one of the things that induced large numbers of people to leave the inner East End in that period.

So I can always understand those who remained there complaining about what happened to the area and saying that it was all a planning disaster, but equally, you can see why people were anxious to get out of an area that appeared to be in kind of constant redevelopment.

What was going on elsewhere was a bit more straightforward. I think gentrification is part of it, but what became more and more obvious to me the more I looked at it, is that there’s no clear cut boundary between gentrification as we understand it and between the sort of large scale conversion of large Victorian houses into flats. There’s a sort of continuum, a constant rebirth of the urban fabric, which runs from classic gentrification to something a lot more mundane. There's no point at which you can say there is a sharp dividing line.

We spoke to John Grindrod a few weeks ago and he was talking about growing up in the suburbs, where (as he put it) “all the poor people in Croydon were shoved out to the edge to be ignored”. I don’t think you could put that down to ‘classic gentrification’. That’s more a symptom of that constant swirl you’re describing.

Circa 1960 there was quite a consensus that you needed to clear slums as quickly as possible, and you didn't waste too much time asking if there was a beautiful Georgian cottage underneath this slum. If it was unfit for human habitation, had an outside loo and no running water, then you pulled it down! Twenty years later the impetus shifted towards doing it up. But mostly that requires private money, and that brings about a shift towards owner occupation.

One of the things that you talk about in the section of the book on eating and drinking is the diversity that was created during this time, and those areas which adopted these very strong ethnic identities. It feels to me that a lot of those areas have remained; that gentrification hasn't quite managed to scrub those off the map.

Yeah, it’s a difficult one. My part of London is Catford and when I was growing up that was quite an early Afro Caribbean reception area, and now there’s a significant Cypriot community and a significant Polish community. It’s extremely diverse. London has become too kaleidoscopic to actually describe in ethnic terms and it probably reached that point 20-odd years ago. It’s become more and more difficult to say “this is an Afro Caribbean area” or “this is a South Asian area”.

Gentrification means a lot of different things of course. It can mean young professionals moving to London and living in places like Catford, which would have been an unlikely place to find them 20 years ago. That kind of gentrification is very different from the bankers moving into purpose built accommodation in Docklands and so on - it’s a completely different social phenomenon, but you can see all different types of gentrification in London.

It’s interesting that you mention Catford, because there was an article recently suggesting that Catford was about to go the same way as Brixton. That it was going to be gentrified beyond recognition.

Well, nowhere is impervious to the flat white invasion. In the book I look at the people moving into Notting Hill in the early 60s. They liked it because it was diverse and had that ‘cutting edge’ atmosphere. Moving to the suburbs was seen as a form of suicide! You were declaring your life to be over. You really wanted to be in the in places like Notting Hill because that was where it was at. Chelsea was even more where it was at until it became unaffordable. While there was almost no gentrification happening in the East End. That’s obviously changed now!

You obviously spent a lot of time travelling around London when you were writing this book. What struck you the most in terms of areas that have changed or evolved?

What seized me the most was that, every time you get on the DLR and go out to Beckton or to Woolwich Arsenal, then something on that route will have changed. And that’s been true for the last ten or fifteen years, since the Thames Gateway area transformed itself. Whereas in South East London, a lot of it is still recognisable to me and it’s had that kind of stability for 60-odd years. It was a ‘first rung on the ladder’ place for my parents and it is for people from very diverse communities today. But riding out towards Canning Town and Beckton on the DLR you see this constant kaleidoscopic change unfold.

Are you optimistic about the future of London, because there's quite a lot going on at the moment in terms of negative news and pessimistic forecasts?

You’d have to say the combination of Brexit, pandemic, and the likely withdrawal of a fair amount of oligarch money is putting the city under a good deal of pressure now.

I don't think you can just say, “Well, we're always saying London’s on the skids and keeps surviving”. But, having said that, I think it will survive this! And to be honest I don't see how any kind of ‘levelling up’ process in other parts of the country is going to seriously diminish London’s standing in the long term. But, absolutely, it does face some real problems at the moment.

You can pick up Waterloo Sunrise from the publishers or via Bookshop.org.

You can read the first chapter of the book here.

News bits

A Met Police officer has been charged with sexually assaulting a colleague in March of 2020, while he was a student officer at Hendon Training School. The officer is due to appear at Willesden Magistrates' Court on 5 April.

Meanwhile the Met is thinking about introducing warrant cards “that can be scanned by smartphones in an attempt to restore confidence in officers”.

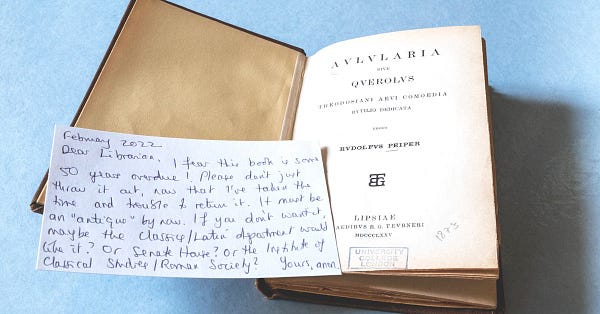

An 1875 edition of a play called 'Querolus', which was due to be returned to the UCL Library in the summer of 1974, has finally made its way back to the stacks after an anonymous borrower returned it with note urging the library not to “throw it out”.

Ben Flatman has been mentioned in these pages before. Last summer the Building Deign columnist was calling London’s skyline “a mess” and asking “Should architects feel ashamed?”. This time around he’s gunning for the East Bank, “the massive new arts quarter” that’s being built over at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. Flatman says that “the disparities between London and the rest of the UK makes the underlying premise and execution look increasingly questionable.” and that it looks like “a fairly straightforward case of cultural gentrification, with seemingly little or no reference to Stratford’s existing culture and community.”

The British Library’s Food Season starts in earnest this week, beginning with an interview with the award-winning food writer Jessica B. Harris and continuing with a panel on the chocolate revolution, a look at food in fiction, and an evening with LiB favourite (and past interviewee) Jonathan Nunn of Vittles.

The National Gallery has changed the name of the Edgar Degas’ drawing ‘Russian Dancers’ to ‘Ukrainian Dancers’, but don’t go along to try and see it, because the turn-of-the-20th-century pastel drawing is “currently not on display”.

A ‘Crested Caracara’ from London Zoo, escaped a few weeks ago after flying away from Regent’s Park during “routine training”. The bird of prey has since been spotted in Putney, and in Streatham Common where it gatecrashed someone’s picnic, and then he seemed to settle in to Mayow Park in Sydenham.

UPDATE: On Monday afternoon, London Zoo confirmed that Jester had got home safe: