Bradley's: Lager and Shots in No-Man's Land

John Bull on how a small Soho bar can be both a home from home and a microcosm of the best of London

Over the past few months we’ve had to write a lot about some of London’s most loved and respected businesses closing down (or having to fight to stay alive).

Of course, there’s always turnover and evolution on the streets of the capital, but that pace has definitely quickened over the past year or so, and the mix of contributing factors seems to have become both more numerous and more merciless.

Sometimes the response to these stories is something along the lines of “Well, when was the last time you actually went there and spent your money with them?” which is both justified and also kind of misses the point. But when we wondered if there was any small thing we could do to try and help push back against this tide, we landed on the idea of a series that highlights some of these smaller, independent businesses; talks about why they’re so beloved by so many; and maybe encourages others to go and visit them before it gets to the point where they have to start some kind of crowdfunding campaign.

Over the next few months we’re going to be visiting some of those places with the people who love them, to talk about what makes them so special. But to kick things off we have this essay by John Bull about the legendary Soho institution, Bradley’s Spanish Bar.

We saw John tweeting about Bradley’s during lockdown (for reasons that will become clear when you read the article) and we have been on at him to turn that thread into an issue for us for about two years now. We’re glad we persevered, because we think it’s one of the finest things we’ve ever published and we really hope you think so too.

Enjoy, and we’ll see you by the jukebox for a drink soon.

“I’m disappointed everyone here isn’t more… you know… Spanish.” The man in the expensive suit says, with slight confusion, to the towering figure behind the downstairs bar. Jan, the Belgian manager of Bradley’s Spanish Bar gives him a look of faint amusement.

Rich, who had been working behind the bar until a few minutes before, is now propping up its end, a glass of cider in his hand.

“If you’re disappointed here mate,” he interjects, in his broad Irish accent, “then you’re going to be really disappointed when you get to the Unicorn down the road!”

His laugh is loud and friendly, and the man in the suit laughs back. I smile, because it’s a joke I’ve heard Rich use before. He likes it because it also makes his underlying point gently clear: despite the name, and the decor, Bradley’s isn’t a theme bar. It’s just a bit odd. Best just to accept it as it is.

That oddity starts with its location. “Bradley’s” (as it is known to its regulars) is in Soho. Yet you could ask a thousand people to point to Soho on a map and their finger would fall nowhere near Bradley’s.

Hanway Street is a skinny slip of road, barely wide enough for a single car. One of the narrow thoroughfares that thousands of people walk past every day but never have a reason to explore. Come out of Tottenham Court Road station, keeping Centre Point behind you, and head north. Look left as you pass the phone shop and you’ll see it, twisting away back round towards Oxford Street. Once you spot it, you’ll always wonder how you missed it before.

Hanway Street is also an oddity, its strange curve and ornate bollards hinting at the reasons why. Hanway is a boundary lane. Go back far enough and it was a border between two parishes. Those parishes are long gone, absorbed into London as it relentlessly expanded west. But their echoes in the city’s bureaucracy remain. So it was that Hanway Street, long before it acquired that name, became the border between Soho to the south and Fitzrovia to the north.

Today, we tend to think of the northern edge of Soho as Oxford Street. The psychogeography of our city has drifted south. This has orphaned Hanway Street and its small network of offshoots to the north, rendering them a no-man’s land between Fitzrovia (with which they don’t connect) and Soho-proper across the bustling, tourist-filled highway to the south. Walk down the street itself and the disconnect feels both palpable and a little bit magical. It’s probably why Neil Gaiman placed one of the entrances to London-below here in Neverwhere. This disconnect, however, is relatively recent. Back in the 1950s, Hanway Street wasn’t the periphery of Soho life, it was briefly its heart.

Coffee and keyfabe

Then, Hanway Street was Soho’s Spanish Quarter. Full of bars and coffee shops from which the sounds of flamenco and Spanish guitar rang out, and occasionally something newer and (if your parents were to be believed) something more dangerous: skiffle.

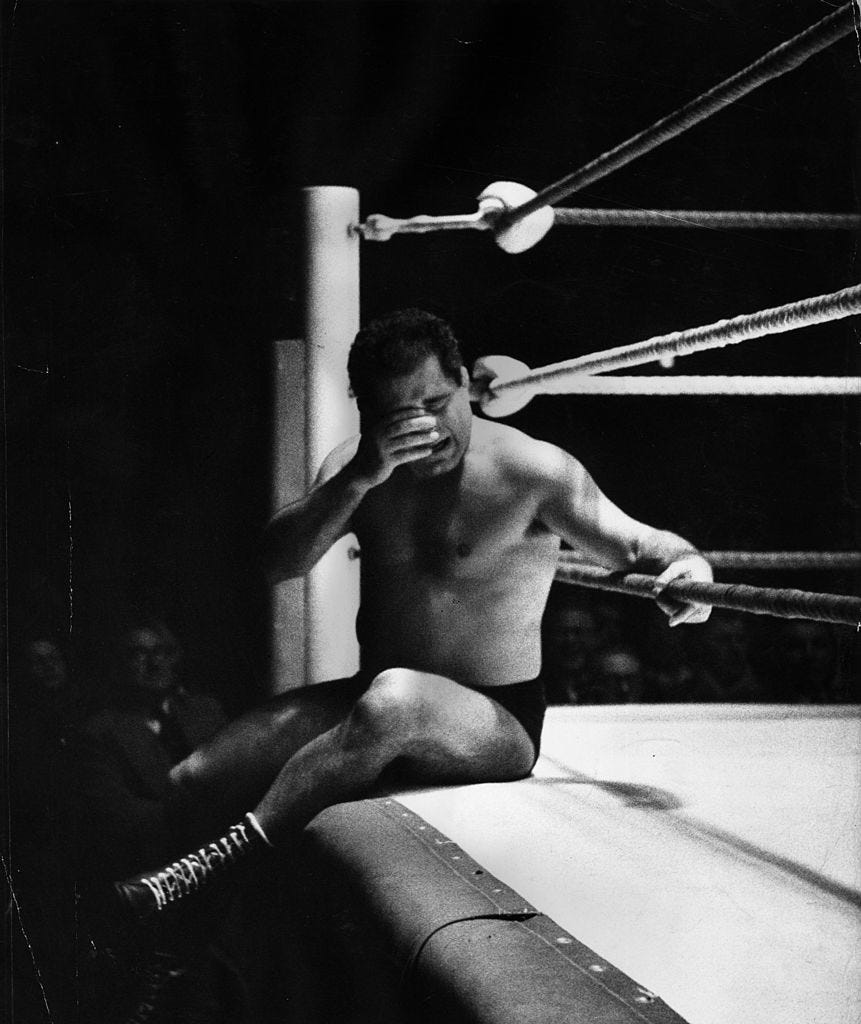

Yet that Spanishness was not quite what it seemed. It owed its origins to three Greek-Cypriot brothers, the most important of whom was the oldest - Milo Popopocopolis. Also known as Milo Popocopolis. Or Mike Prince. Or Milo the Greek. Or The Golden Greek.

Milo, if you have yet to guess, was a wrestler.

Milo had arrived in London in the early fifties with nothing but a suitcase and some talent in the squared circle. By the middle of the decade he had firmly established himself on the British wrestling circuit and invested his earnings in property, buying his way into the burgeoning (and not always entirely legal) Soho nightlife scene. His brothers Johnny and Tommy soon joined him in the UK and so it was, in 1952, that Milo set them up at No. 22 Hanway Street with a coffee shop.

At this point, we enter the realm of legend and memory, as much as history.

Over the years I have drunk in Bradley’s I have heard many different accounts of both the bar’s and Hanway Street’s history, which are inseparably linked. None of them are true, but none of them are entirely untrue either. The “Milo brothers” (as they often referred to themselves) were wrestlers and wrestling is a world built on keyfabe - the principle that reality is malleable and that a good narrative is as important as the truth. The brothers full embraced this on Hanway Street.

The keyfabe version is that Johnny’s wife was Spanish and Johnny persuaded Milo that a Spanish cafe would go down well. Thus, the seeds of Soho’s Spanish Quarter were sown - from Greek-Cypriot hands, but authentic seeds.

The reality is different, but you have to go all the way to Spain to hear it. The Spanish writer Victor Fuentes, then living in London, was a barista at this first Hanway coffee bar just after it opened. He remembers Johnny being obsessed with loud shirts and the Betty Gable film Diamond Horseshoe, released to the Greek market as Acapulco. That was enough reason for Johnny to theme their new cafe around Spanish culture - especially as there was a large Spanish Sherry and wine importer a few doors down the road.

And so, the wrestler Mike “The Greek Adonis” Demitre (actually Canadian, of course) who dabbled in interior decorating was invited to do his best impression of Spanish design on the site and Acapulco Coffee Bar was born.

Then, as is so often the case in London, something wonderful and natural happened. Fuentes watched as, over time, Spanish exiles latched onto something, anything that reminded them of home and - with their patronage - the tiny and now authentic Spanish quarter was born.

Which brings us back, finally, to Bradley’s itself and again to legend and memory.

What’s in a name?

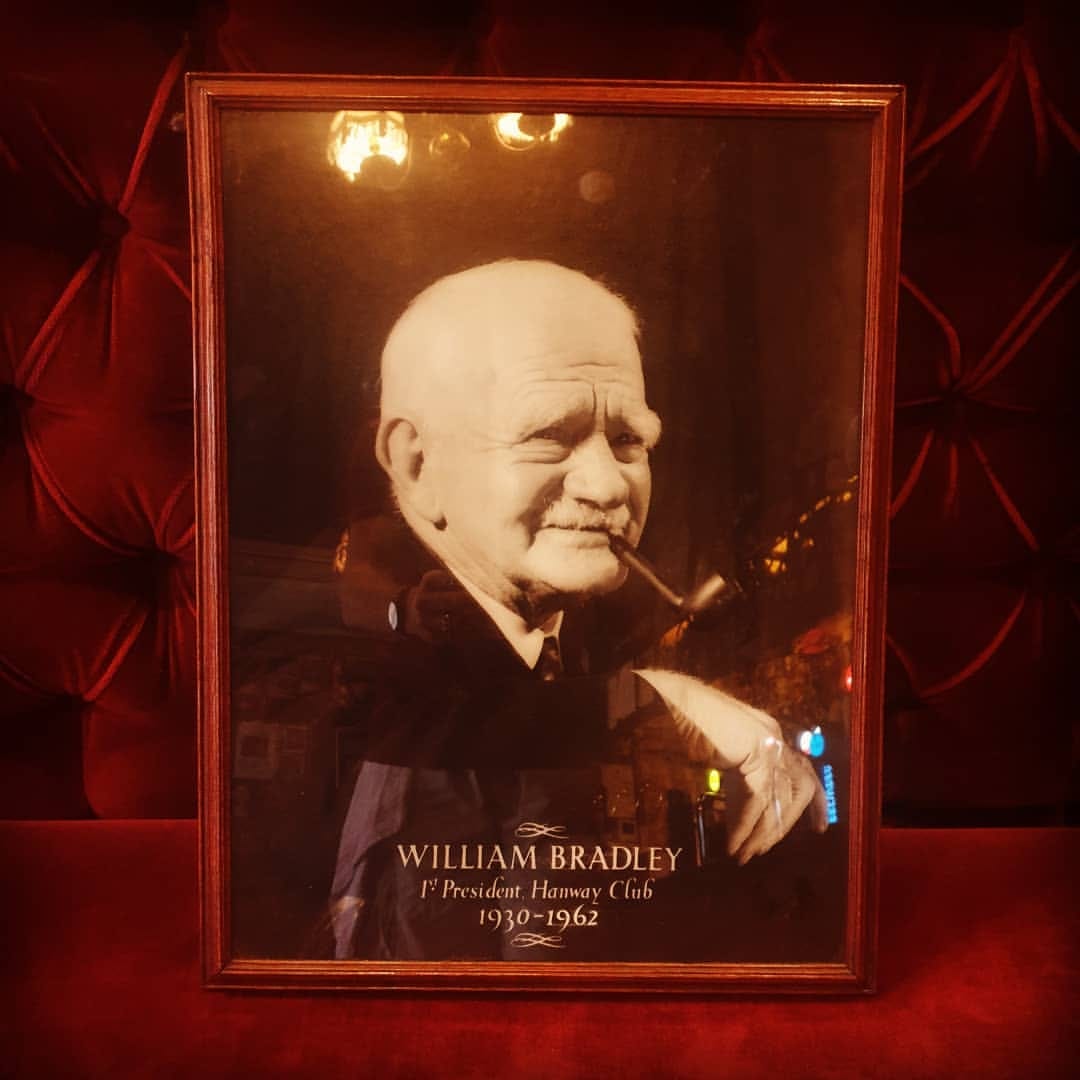

William Bradley was the manager of a glass works on Hanway Place. For decades William had used the downstairs of the Sherry and Wine importers as the site of a social club - one that started out just for his workers, but was soon open to anyone who knew it was there. In the 1960s, so the legend goes, William persuaded the Milos to buy the now-troubled Importer’s premises and turn the bar into something official. Thus “Bradley’s Spanish Bar” was born.

Keyfabe again. A whisper of truth buried in a good story.

Tax records don’t tell us exactly when the Milos purchased the bar. As with many in Soho at the time the Milo’s relationship with the revenue services seems to have been somewhat fleeting. We have phone directories though. In 1968 ‘Short’s Wine Merchants’ still appears in them, but by 1969 the same number is listed as… “Bradley’s Bar”

And to me, that’s arguably more interesting than the legend, because William Bradley died in 1962. There was no William Bradley around to persuade the Milos to save his preferred drinking spot in 1968, just - I have come to suspect - the community of drinkers he had left behind.

Perhaps the Milos were part of that community. They would certainly take seriously their role as Bradley’s guardians for the next few decades and beyond. Perhaps they saved it not just because they spotted a business opportunity, but also because to them, and for others, it had become a home from home. It would explain why, once they had the lease, they may have chosen to name it after the man who had brought them all together.

William Bradley may have died seven years earlier, but the warmth of his memory remained.

Life support

This brush with closure was something I found myself thinking about a lot during Lockdown. Throughout the pandemic, Bradley’s shutters remained firmly closed. Behind them, Jan the bar manager was pouring away beer by the gallon and (over WhatsApp) he confided with some of us that things were looking dire. Bradley’s has never been about making money and its owners have never been rich. Certainly not rich enough to cover rent, bills and wages through a prolonged closure.

Bradley’s, it seemed, was about to die.

As much in hope as expectation, Jan created a fundraising page online, circulating it among the regulars he could reach. In April 2020 I shared a link to it on Twitter in the hope of reaching more. In anger and frustration at what we all thought we were losing, I found myself trying to explain on social media just why this bar was a bit special. I didn’t expect anyone to care. What’s another obscure London bar lost to the world?

But then an odd thing happened. The money started coming in.

In hindsight, maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised. Every generation of drinkers likes to think they are the first to call their particular bar home, but we’d all forgotten that Bradley’s has been around now for a very, very long time.

Like an alcoholic Bailey’s Building and Loan, it turned out that we were not alone. Five generations of drinkers had invested a small part of themselves into Bradley’s. All of them, like us, felt we had received back more than we had put in. From Australia to America the stories - and people - came out of the woodwork. The artworkers. The theatre workers. The sound workers. The writers. The musicians and actors. Soho residents, workers and exiles, all of whom shared one thing in common: that, at some point, we had called Bradley’s home.

And so Bradley’s was saved through the generosity of its former patrons, its regulars and others who perhaps hoped for the opportunity to become patrons in future.

Coming up on Wednesday 🎥

In our subscriber-only edition this week, it’s the latest installment of our Electric Theatre column, which looks at London on film. This month it’s a classic slice of 80s London noir.

Subscribe to LiB now and that will be in your inbox first thing on Wednesday.

Grubby magic

If you started reading this article expecting a description of what Bradley’s looks like, then by this point I owe you an apology. Because the truth is that there isn’t much to see. It’s just two small rooms - ground floor and basement - in a brightly-painted, slightly run down building tucked away from the London fray. That’s not to say it isn’t pretty. Upstairs you’ll find a gloriously maintained 1970s jukebox and walls littered with a mix of art, photos and Spanish kitsch among which a large, framed photo of William Bradley himself takes pride of place.

Downstairs is darker and gloomier. The narrow stairway tends to keep the stag and hen parties away. The lack of space downstairs is, to those who drink there, a feature not a bug. It makes it a place for meeting one or two friends and close conversation, not holding court. Upstairs is brighter and more glamorous. The Instagrammers that occasionally seek out the bar these days certainly prefer it (the lighting is better).

But Bradley’s isn’t - and has never really been - about the place. It’s the living history it embodies, the stories and memories that have been (and still are) born there. It’s about drinks huddled round a small table with friends or a casual pint at the bar. It’s about the times you pop in with a book for a quiet drink and find yourself still there five hours later, chatting to three people you already knew, and a random passerby who popped in two hours earlier to avoid the rain. Or, on particularly quiet days, it’s a handy place to dive into and just suck in its atmosphere. It inspires you to think. And to write.

As I’m doing now.

Closing my laptop, I pick it up off the broken Pacman machine (it’s never worked as long as I’ve been drinking here) that was doubling as a table and place it in my bag. My pint is downed and I start up the stairs, calling out a goodbye to Jan and Rich at the bar as a go. I’m two steps up before a shout beckons me back. One of the other regulars has ordered a round of Jägermeister shots and I’m included in it. It’s a Bradley’s tradition (earlier, I bought a round myself) and… well, it would be rude to say no, wouldn’t it?

One for the road then.

My second attempt to escape is more successful. A light mist of rain floats over Hanway Street as I leave and I breathe it in deeply. I can’t help it. It’s instinctive. There’s something unique about the way London smells - about how it feels when it’s raining.

I remember trying to describe it to my father once, at our old family home out in the shires. We were sitting on his covered patio and it had started raining, heavy drops drumming on the plastic roof and running down the wooden supports to pool in puddles on the grass. He’d made a comment about how fresh it smelt and then a barbed one about how different London must be in the rain.

He was right, of course. It is different when it rains here. But not bad different. Just different. Special. And outside Bradley’s, you can really get the sense of why. The diesel fumes of buses mixes with the fresh smell of ozone to create air you don’t just breathe, but taste. On the street below, you can see the faint shimmer of ever-changing colour in the water as it flows down the road - the grease and dirt mingling to make something grubby seem briefly magical. Then there’s the sudden, unexpected whip of rain and wind under your coat from the corner with Oxford Street nearby. You’re so close to what outsiders believe London to be, yet somehow so far away from it at the same time.

London in a bottle

In a way, Bradley’s is a microcosm of how community works in this city. Every time I leave, I feel it. And every time I try to bottle that feeling of how interconnected with the city you become in these moments, so I can finally explain it to my father.

But I can never find the words. The one time I tried, I realised I was making the city - my city - sound dystopian, not Utopian. All I was doing was confirming everything he thought was wrong with London, even as I was trying to describe the things that make this city and its hidden places my first and forever love.

The first time I ever felt this way was outside a bar in Soho. It was at that moment that I really knew that I was a Londoner, not just another person passing through. The city had penetrated my skin and seeped into my veins without me even noticing. I knew that in this weird but beautiful city, where you can feel both anonymous and included at the same time, I had found a home.

It was not this bar. Just one of so many that are just a memory now - a plaque on a wall or a quirky-shaped block of expensive (and often empty) apartments off Poland Street. But it is Bradley’s that makes me feel this way now and as I look around and see the creeping signs of redevelopment on Hanway Street, as I remember the perilous days of Lockdown, I realise with a pang of fear that maybe Bradley’s won’t survive much longer.

But then that’s what William Bradley himself probably thought about his little drinking club back in the fifties.

As I pull up my hood against the weather and step out into the cold London night, I take comfort in the fact that he was wrong about that.

So maybe, just maybe, I’m wrong too.

John Bull is a historian, writer and streamer who specialises in history that falls through the gaps. From the quirks of international law that led to the Knights Hospitaler possessing one of the largest airforces in Europe after WW2, to the secret Foreign Office scheme that allowed 40,000 Jews to escape Nazi Germany, John specialises in telling these stories concisely, but accurately and without hyperbole, for general audiences. You can find him on both Twitter and Mastodon.

He is also the author of The Brexit Tapes: A Satirical History of Brexit, available in all good bookshops (and Amazon). He is currently working on his next novel The Goblin Launderette, a fantasy novel about love, loss, magic and laundry.

5 little bits

The Met has blocked “access to TikTok and other social media sites” on officers’ phones. It’s not clear if they’ve been banned for security reason or because officers can’t be trusted to use them without being abusive in some way. However, WhatsApp was “not included in the list of blocked apps… although using it could only be on a restricted basis and with express permission from managers.” Meanwhile, Sadiq has written a letter to Grant Shapps to say that Wayne Couzens shouldn’t get his £7,000 a year police pension (he’s written to the Energy Secretary because Couzens worked for the Civil Nuclear Constabulary, and they’re run by the UK Atomic Energy Agency).

Over the weekend, The Times reported that the Forset Court block of flats next to Hyde Park, “is believed to be accommodating as many tourists as the Ritz Hotel” as around 90 per cent of the 118 properties it contains are being rented out as holiday stays on “Airbnb-type” sites.

The antisocial theatre audience trend continued last week, when a performance of Bat Out of Hell at the Peacock Theatre “was halted for several minutes” after an audience member who was “talking loudly throughout the performance and being quite disruptive” was asked to leave the venue.

According to research published last week in Environmental Pollution (later reported in The Guardian), grey squirrels suffer “worsening lung damage the closer they live to the centre of a city,” while those that can afford to live in areas like “leafy Richmond” have a longer life expectancy.

Bill Gates posted an article to his blog the other day about autonomous vehicles. The article contains this video of Bill putting a driverless car “to the test in downtown London,” which, as far as we can make out, means the Caledonian Road and Victoria Embankment: