Electric Theatre: The Jokers (1967)

Mike Sizemore joins Michael Crawford and Oliver Reed as they take on London

Electric Theatre is our monthly, rotating column where we invite some of our favourite people to write about London on film. It’s an opportunity to look at how the city has been represented on the big screen over the years, how its landmarks and icons have been used (and abused) and how various genres and directors extract wildly different performances from its streets.

For the first instalment of Electric Theatre we’ve invited Mike Sizemore to write about one of his favourite London films. Mike is an award-winning screenwriter, writer and graphic novelist who has most recently been working with John Carpenter on a series of comic books. We expected Mike to come back with a pitch about a film involving spaceships and/or chainsaws, but he surprised us with a 60s comic caper starring the Phantom of the Opera and Bill Sykes. It’s a corker.

Welcome to the Electric Theatre. Please turn off your phones and refrain from talking for the duration of the entertainment.

Michael Crawford is breathless and panting when Oliver Reed catches up with him and before he can get a word of explanation out, he’s picked up by one ankle and finds himself hanging upside down over one of the fountains in Trafalgar Square.

The sun has just set, it’s July 1966 and, as far as Reed is concerned, this is the last time Crawford is going to run out on his bar tab without paying. There’s no animosity in it. They’re co-starring in a new movie called The Jokers and it’s going well, but Reed takes his reputation in Soho’s bars very seriously and has had enough with the younger man’s habit of sliding off just before the bill arrives.

Looking at his reflection in the water a few inches from his face, Crawford can now see his mistake and starts to scream. The pair are soon joined by their director, Michael Winner, who moments ago had won a bet with Reed that Crawford wouldn’t pick up the cheque at The White Elephant Club (now the private casino, Aspinalls, on Curzon Street) despite the fact that Crawford was the one who invited them there. Right now Winner is more concerned with the fact that that Reed is about to get Crawford’s tuxedo soaking wet while they still have a night’s shooting ahead of them. To the director’s relief and Reed’s sense of justice, Crawford manages to hand his wallet over while still inverted and the matter is settled.

They make an odd pair, Reed and Crawford. Thin chalk and broad cheese, but there’s a spark there. Crawford couldn’t see it at first when director Michael Winner suggested his new favourite actor for the role of his ‘older brother’. He’s too different. We’re nothing alike. What about Stanley Baker instead? But Crawford begrudgingly took a meeting and in walked Oliver Reed with his own younger brother: tall thin and gangly. Chalk and cheese. Crawford laughed and the part went to Reed.

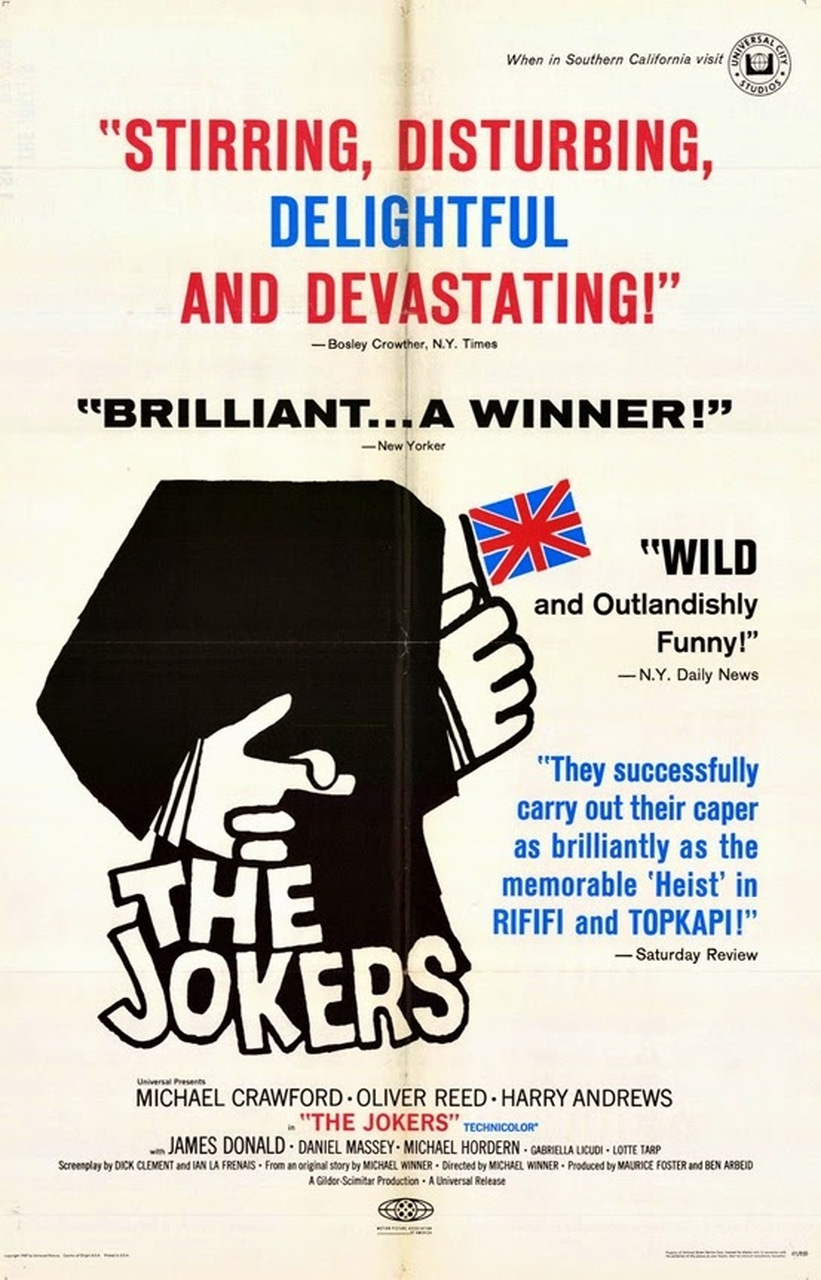

It’s lovely casting. The Evening Standard even went as far as to declare the pair the new Laurel and Hardy. They’re not, but the chemistry is in every scene they share and it’s one of the best things about a movie that has sadly fallen into neglect despite being one of the biggest hits of year when it was released, with rave reviews on both sides of the Atlantic.

Dip into interviews with Reed, Crawford and Winner from the time and there’s even talk of a sequel. Sadly that never came to pass, and the next time the two stars would act together was almost fifteen years later in Disney’s Condorman. Crawford painfully killing an American accent as Reed joyfully hams it up with what he believes is a Russian one, in a movie that Disney for some reason hasn’t seen fit to make room for alongside its more chiselled MCU superheroes on Disney+.

But back to The Jokers. The plot, whether you’re a fan of caper movies, classic British comedy or swinging 60s time capsules, is a cracker.

Two brothers, Michael (Crawford) and David (Reed) Tremayne feel confined in their safe but dull upper-class surroundings, and are searching for a way to make their mark and seek the recognition they believe they deserve - as long as it doesn’t involve actual work.

Both lean more towards pranking and subverting authority so, influenced by the recent Great Train Robbery, they hit upon the kind of stunt (“A grand gesture!”) that will make a splash in the papers without also landing them a jail sentence.

Their big idea is to exploit the kind of legal loophole that sounds like it could only ever work in a movie, but was in fact a ruse that Winner himself used at university. After learning that a person can only be charged with theft if they permanently deprive the owner of their property, they send letters to their solicitors stating their intent to steal along with a promise to return said stolen property one week later. Cue a swinging tour of London cultural hotspots before they hit upon the prefect target: Her Majesty’s Crown Jewels.

How they pull off the impossible heist takes up much of the movie’s running time and is a thoroughly enjoyable romp written by Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais (The Likely Lads, Porridge, Auf Wiedersehen, Pet etc). It offers a luscious glimpse back into the capital of 1967 with some lovely candid photography. When refused permission to continue filming inside the Tower of London itself, the cast simply turned up as tourists with hidden cameras to grab the shots they needed.

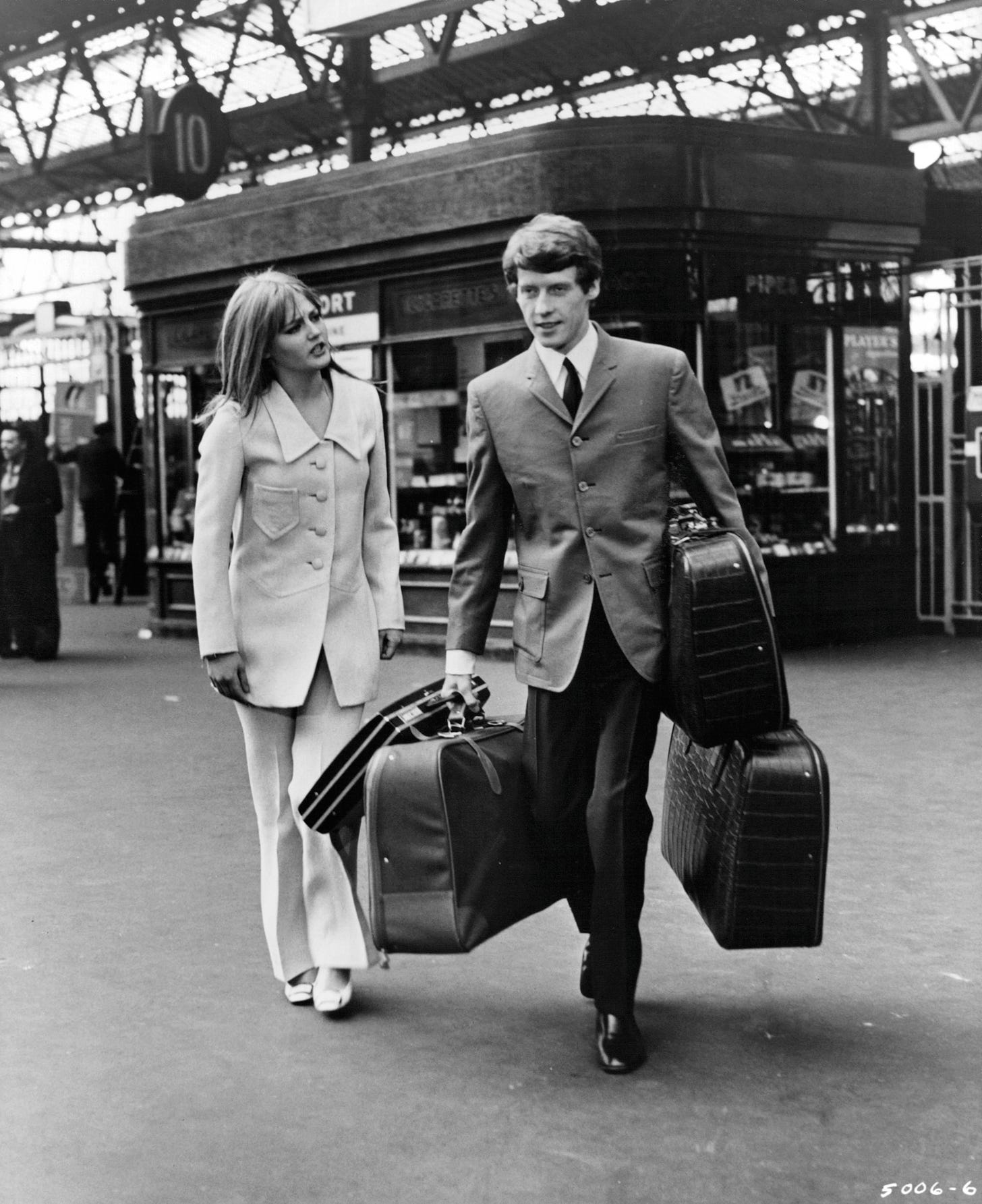

The interior of the Tower shown in the climax of the robbery is actually Hampton Court Palace, which didn’t mind hosting the bomb squad, the Met and a few controlled explosions. You also get to take in the Albert Memorial, London Zoo, the Stock Exchange, Downing Street, Waterloo Station and the Old Bailey, an absolutely spiffing cricket match in SW3 and a night time jolly on the Thames.

Other locations were a little harder to secure as Winner already had a reputation for creating havoc in the city. While shooting You Must Be Joking a few years earlier, he’d exploded a Rolls Royce in Piccadilly Circus and the powers-that-be unsurprisingly frowned upon that kind of thing. Here’s how he described the experience himself in his (first) autobiography:

“We made The Jokers on locations all over London with some difficulty as the police weren’t mad about me. But in those days they took bribes galore. I was shooting just off Sloane Street once. We had the unit base in the garage. It was night and I could see all the lights turning on in a block of flats as residents phoned the police to complain about the noise. Policemen came round to the garage where the unit were set up for dinner. The location manager gave each one five pounds and they’d sit down and have a cup of tea.”

A tenner wasn’t going to cover the chaos Winner created later in the shoot when, without telling anyone, he let off a smoke-bomb in Piccadilly Circus causing a huge traffic jam and the police to arrive and arrest the crew. Winner himself escaped under cover of the smoke, with the footage under his arm. After the stunt made the national press the next day, a complete ban on movie filming in the area was imposed that lasted fourteen years until an American Werewolf crashed out of a porn cinema in 1981.

The movie was a tremendous hit (which makes its current unavailability even harder to fathom) and acted as a springboard for the carers of Winner, Crawford and Reed. Gene Kelly declared it “the most wonderful film I’ve ever seen” and Orson Welles subsequently struck up a lifetime friendship with both Winner and Reed. Crawford’s subsequent nationwide fame with Some Mothers Do Ave Em overshadowed his earlier, quirky film career (How I Won The War, Hello Dolly!), but it did allow him to become the masked guy in the rafters, selling CDs by the truckload.

There’s a perfectly watchable copy of The Jokers on YouTube, but you may also have some success tracking down an older, out-of-print DVD until some noble company releases the high definition 4K version I dream of, and which will finally flood the film with real colour.

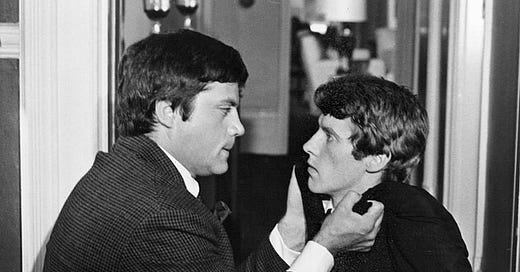

For now though, do look out for the scene towards the end of the movie where Reed is scripted to tussle with his younger brother and, living up to his larger-than-life reputation, decides to go all-in; causing Crawford to reminisce in his autobiography:

“His ham-like hands were fastened so tightly round my neck, I felt the end of my life was imminent. It took four people to get him off me - and only two of them were scripted.”

I’ve saved the best bit of Jokers trivia til last.

Winner, never one to pass over a good opportunity for free publicity, hit upon the perfect way to publicise the movie for free. Two students at Cambridge had recently made the press by somehow getting a Morris Minor up onto the roof of King’s College Chapel and this had stuck with Winner so much that he decided to add the anecdote to his script.

The day after the movie opened he hired a private detective to track down the students and provide them with ropes and grappling hooks so they could head to the Tower on the very day the actual Crown Jewels were being moved to the newly constructed Jewel Room.

Along with the regular Beefeaters, the place was crawling with extra security, police and a few hundred troops. The kids waited until the early hours of the morning and then they scaled the Tower’s walls and deployed a banner advertising the film. Winner’s plan was for the students to get caught, causing a national outcry. But unfortunately for him they were too good at their job and they walked away from Tower unapprehended.

Outraged, Winner took it upon himself to call the press and confess he had the boys who had broken into the Tower of London. Meanwhile, oblivious staff at the Tower only found out about the raid when a newspaper reporter rang and got someone out of bed to ask them about it. I don’t think they got the joke.

You can find Mike on Twitter and on Instagram.

If you have a favourite example of London on screen that you want to write about for Electric Theatre, then send us a pitch at londoninbits@gmail.com.