How to design and build a more sustainable London

Harriet Thorpe on what it takes to make a city truly sustainable

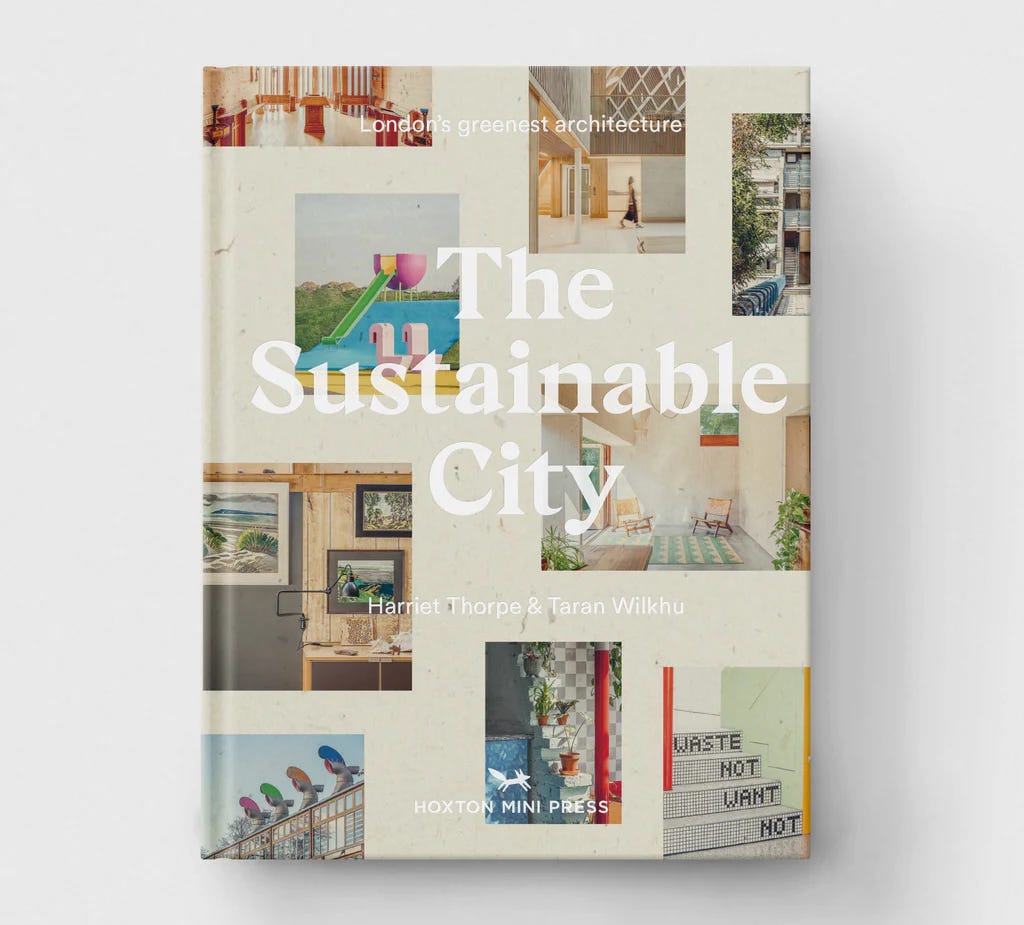

The journalist, writer and editor Harriet Thorpe recently teamed up with photographer Taran Wilkhu to produce a new book for Hoxton Mini Press, called The Sustainable City.

In the book Harriet tours some of the more innovative and forward-thinking developments from across the city, looking at the kind of urban architecture that not only benefits the people who live and work in them, but also the planet as a whole.

In this article Harriet sums up what it means to be a sustainable city and explores how London’s buildings can help reduce our carbon footprint, combat gentrification, increase prosperity, preserve history and inspire the people who live and work in them.

Cities are a great idea and, in general, living in a city is a more sustainable choice.

Not only do they encourage a shared and more efficient use of things that take a toll on our environment (things like transport and heating), but also the population density of cities helps to keep the countryside green, as it should be.

The problem is that cities aren’t growing sustainably. Globally that means slums are increasing and pollution is growing alongside other dangerous things (See UN Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable). This means that, even though they occupy just 3 percent of the world’s surface, cities currently account for about 70 percent of global carbon emissions and consume over 60 percent of global resources.

So what exactly are we aiming for here? What is a ‘sustainable’ city? Well, first it must provide the basics: safe resources (like clean water), functioning services (like paths and roads) and affordable housing (shelter). It should present dynamic opportunities, shared prosperity, social stability and make environmentally-friendly living an easy choice for its citizens.

In short: Rather than sucking our earth dry, it should actively help to repair, enhance and contribute to the regenerative health of our Earth.

London is certainly progressive in its approach to becoming more sustainable. Its ‘Ultra-Low Emission Zone’ tackling vehicle pollution seems to be working (see this recent Bloomberg article on its progress), it has bicycle-sharing schemes, an efficient public transport system, and 3,000 parks across the city.

However, there is much room for improvement. Buildings are wasting energy, leaving 398,000 London households in ‘fuel poverty’ (defined as those households where spending what’s required on fuel leaves them with an average income below the poverty line). London also generates vast amounts of waste (seven million tonnes each year) and 16 percent of major roads in the capital still exceed the legal limits for nitrogen dioxide, one of the main contributors to air pollution.

These issues are affecting people’s health across the city: life expectancy differs by up to 19 years between boroughs, with the largest disparity between some of the richest and poorest people in the UK.

It’s important to see the health of people at the very heart of the ‘sustainability’ issue – people (like trees, the air, and the soil) are all part of the eco-system. Making everyone’s lives healthy and happy is the very reason why we should all be working together to make this world more sustainable.

In The Sustainable City we ask how good architecture and design can help solve some of these problems that London has, and profile some of the people who are part of the process, from problem-solvers to residents. Here are just a few topics that are explored in the book to get you thinking about the built environment of the city – from the temperature inside a building, to how well a building is designed to enhance your life, and what a building is made of…

Reduce energy bills by design

Because energy used to be cheap, many buildings weren’t designed to preserve it. But a building can be designed to use as little energy as possible. For example, ‘passive’ design principles harness the natural qualities of materials, climate and science and use them to a building’s advantage, to keep it at a comfortable temperature all year around. Many of these principles have been used for centuries in architecture – way before we relied on radiators and air conditioning.

Commissioned byCamden Council, Agar Grove is the first large-scale inner-city residential Passive House development in the UK. The Passive House Standard (also known as ‘Passivhaus’ due to its German origins), sets out guidance for a building to reach the lowest energy consumption possible. This can be affected by things like the size, orientation and design of a building’s windows or how much insulation it has. The Passive House design at Agar Grove results in a 70 percent reduction in energy demand compared to the previous homes on the estate.

In the case of Agar Grove, some existing buildings were demolished to make way for new Passive House homes, while the tallest building on the estate was retained to be retrofitted. ‘Retrofitting’ a building can improve its energy efficiency, for example properly insulating a badly insulated building can reduce its heating demand by up to 80 percent. The UK has a huge problem with poorly insulated and draughty homes, and when 80 percent of UK homes that will be in use by 2050 have already been built, government policy needs to focus more on improving what we have (instead of ‘build, build, build’).

N.B. If you have a draughty home and can’t afford a renovation, you might be interested in campaigning for this cause. Households Declare from the Architects Climate Action Network is an excellent resource and campaign for just this.

If possible, it’s usually more sustainable to try to improve a building than to demolish it. This might change in the future, but we are in a climate emergency right now. Statistics from 2018 show that, in the UK, 62 percent of waste is made up of construction debris. Improving that statistic means buildings and materials need to be repurposed instead of wasted at all scales.

An old council office destined for demolition could become a unique luxury hotel (see The Standard in Kings Cross); a house renovation could employ its own construction waste in its new design (see architect Mat Barnes’ Edwardian house in Sydenham); or a building could be designed like a flat-pack, to be rebuilt elsewhere in the future if the city no longer needs it (see the Oasis Waterloo Farm) instead of being demolished and its materials wasted.

Inside the book you will find so much creativity when it comes to ‘adaptive re-use’ (as it is termed in the architecture world) and, as well as sustainability, it preserves the city’s character and built heritage too.

Design workspaces that contribute to anti-gentrification

When a building is designed – if it is done well that is – it is designed with careful research into the surrounding context that flows around it. Buildings can be designed to be environmentally-friendly in themselves, yet their design can have a huge sustainable impact that radiates out into communities – from a bike store or a buggy store that makes cycling and walking easier for its visitors, to a green roof that provides a stop-over for birds between parks.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to London in Bits to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.