John Grindrod on Docklands, the Dome and giant eggcups

Part two of our conversation with the author and architecture geek

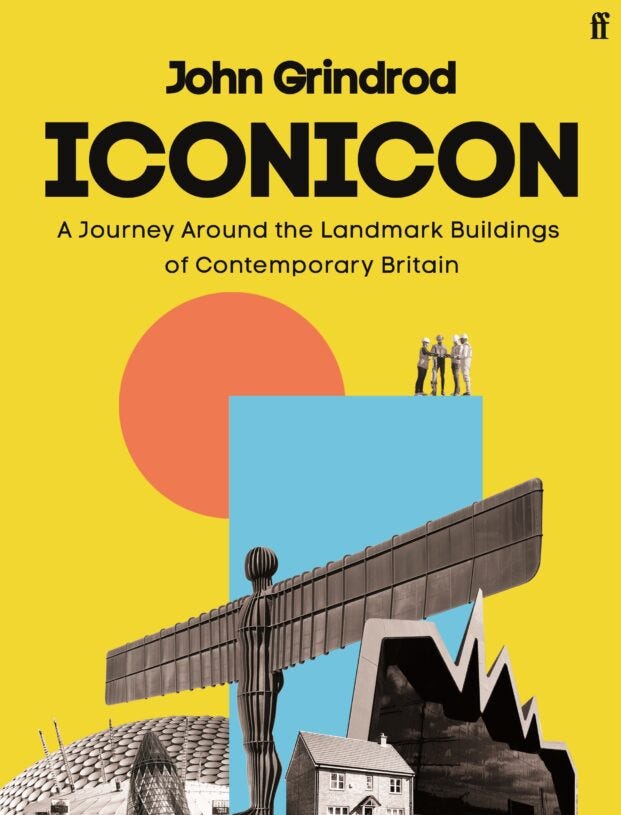

This is the second part of our interview with John Grindrod, the author of the books Concretopia: A Journey Around the Rebuilding of Postwar Britain, Outskirts: Living Life on the Edge of the Green Belt and the brand new Iconicon: A Journey Around the Landmark Buildings of Contemporary Britain.

In the first instalment, which went out last week to paying subscribers, we spoke to John about growing up in the suburbs of New Addington, his love for council homes, and how the pandemic is altering the look of London:

Today we talk about John’s brand new book, Iconicon (which has been picking up some great reviews), some of the more unexpected London icons he has chosen to write about and what he thinks is “the worst possible bit of London”.

Would you say your new book, Iconicon (above) is a kind of a sequel to your first book, Concretopia? A continuation of the story you started then?

Concretopia was the first book I wrote and I didn’t know what I was doing when I wrote it. I was quite naive. I had a full-time job and I thought I could just write a panoramic history of Britian’s post-war architecture in my spare time. But it was really hard work, and it’s sort of amazing I even did it really! I feel more confident as a writer now and more confident in having a voice. So in terms of the subject matter it’s a continuation, but in terms of the actual writing I think it’s probably a bit better.

When I wrote Concretopia I thought I’d finished telling that story. But so much has happened since then. We’ve had the Olympics, we’ve had Grenfell, we’ve had the pandemic. They really feel like a horrible full stop to a period which felt, in my head at least, was just going on and on and had no real shape to it that I could see.

The pandemic has meant that we’ve all stopped travelling around so much and we’ve all got used to our local areas again and that moment of reflection, of looking to see what’s actually happened to where we live, is quite interesting.

I think a lot of us have paid more attention to that than maybe than we ever had done. So that became a sort of a ‘backwards shadow’ over the rest of the book and became a way of trying to process things like Docklands and all those Millennium things and business parks and shopping centres, and retail parks and Barratt Estates.

What I realised when I was writing the new book was, it’s basically the same story as Concretopia, but in reverse. So in Concretopia we start with the war and as we’re coming out of that there’s all of these revolutionary things, like the NHS and the welfare state, that begins to change the way that we’re going to live. There’s the architecture that happens as a result of that ambition of trying to create a more equal society, and then there’s the financial collapse in the 70s and everything gradually grinds to a halt. Then we have the pivot moment of the Thatcher government coming in with right-to-buy and suddenly selling off all that council housing that’s been built.

Right now, it’s suddenly like we’ve gone back in time to 1939, to that era of patrician largesse where you can only have good stuff if some private individual bestows some money on something, because the government has stepped back and isn’t providing any of that stuff. And as a result we’re in a really unequal society that’s being ruled by a load of Etonians, in the same way that we were in the 80s. It feels like some sort of horrible ‘butterfly wing’ mirror image of where we were.

You’re making the new book sound very gloomy! There must be some positive things in there.

One of the great things about writing the book is that finding out all these great stories from the people I interviewed. One of the things I lived through but didn’t realise was quite as amazing as it was, was all the millennium stuff. Basically, we had 27 versions of Guggenheim Bilbao being built all around Britain at the same time. And it turns out most of that stuff was great. At the time everyone was saying “Oh, it’s all a disaster and it’s going to be a failure”, because as a country we are just rubbish at enjoying ourselves.

Interviewing Mike Davies who designed the Dome, was phenomenal and hearing stories about some of the designers who were building the zones in the Dome. That stuff was just brilliant.

We saw this when the Dome got ripped apart in the storms. You only had to look at Twitter and see there was no gloating going on and that everyone was quite upset!

Exactly, everyone is so invested in this building now and it's part of our lives as this optimistic symbol.

That moment was also a reminder to me of how transient writing about all of this stuff is. Because the new book was all printed when the storms happened. So already history is happening and all that stuff is sort of out of date. You can never quite keep up with the world!

What’s the story that you wanted to tell with the new book? Did you know the point you were setting out to make, or did it evolve?

The book is called Iconicon partly because this has been the era of the architectural icon and people want an icon to brand a place. I guess my theory with this book was that they are not the only kind of icons and that some of the icons that we’ve ended up with - like Barratt Estates - are icons of other things. They are icons of somebody’s ambition for our lives, or they’re icons of taste, or of domestic life, or of what a private developer is willing to build for us.

I felt like it’s easy to just take the things that we are told are icons as the definitive list. But actually a retail market is just as much of an icon of the way that we live in a moment in time. Barratt Estates are an icon of the eighties. They tell you the story of the eighties every bit as clearly as Duran Duran or Margaret Thatcher.

It’s the same with all those millennium things. There were some massive projects, but then there were also some really small millennium things. There are all sorts of tiny millennium monuments that happened, which are a reminder that it's usually not the great big stuff that tells you the story of your life.

The Shard has no connection to my life, even though I travel underneath it most days, it means nothing to my life in the way that a lot of business parks I have worked in might do.

Which London based icons are in the book? The ones that people might not already see as icons.

The whole first section has a continuing thread about Docklands, because it’s a story of almost constant erasure and creation. Even some of the early things that got built there during the regeneration of Docklands in the 80s then got demolished and get replaced by even bigger stuff a bit later on.

Also it’s a strange place because it’s been built according to what rich people wanted to build on the plots of land that they bought, rather than a planning authority saying “We need some shops and local amenities”. You can’t buy anything there. Friends that used to live there would complain that, if they wanted a newspaper then they would have to walk miles.

I also interviewed Terry Farrell about Charing Cross station and MI6 and ‘Eggcup House’, TV-am’s building. That was great. He’s got one of the giant egg cups from the roof of Egg Cup House in his flat (above), which is amazing.

At the beginning of the eighties. He had this tiny practice of something like 15 people and then he got these three mega commissions in London. Alban Gate in the City, Charing Cross station and MI6.

It’s strange to look back now to the pre-MI6 Vauxhall. The arrival of that building and the ambition there was for that area… And then look at what we have in Vauxhall now.

I think MI6 is a good building. Whereas St George’s Wharf is an absolute abomination. It’s like the worst possible bit of London. That is oligarchitecture isn’t it? That whole stretch up to Battersea Power Station is absurd, which is a real shame. But the MI6 building is brilliant I think.

What’s fun is, Terry Farell was telling me that he didn’t know that it was for MI6, and they kept saying it was for the Department of the Environment. It was only when it was finished that he turned CNN on and he found out. The Kremlin declassified the KGB’s office and admitted that they existed so, as a result, the British Secret Service said “Oh well, we exist too… And we’re here!”

You return to where you grew up in this book. How was that?

The last chapter of the book is about Croydon and I end up going back to New Addington.

New Addington has its own icon which has just been built. It’s a leisure centre, which has got this great big, floating, illuminated glass box above it. In the book I say it looks a bit like Independence Day, like some kind of giant spaceship flying over the town. It's really weird. But on the back of it, attached to the back of the building, they’ve built eight houses and they are right underneath the air vents. So they’ve got little roof terraces with this air vent making this terrible whirring sound at them. It’s an extraordinary, weird bodge of a thing.

One of the other places I talk about in this book is BedZED in Beddington. It’s Britain’s first zero energy development that was built in the late 90s. It's incredibly cool and fun and friendly place. It’s sort of like the Good Life as a high-tech sort of utopia.

It’s absolutely amazing. I mean, it’s up there with the Barbican as an incredible bit of modern architecture in London and most people don’t know it exists.

You can follow John on Twitter or you can catch him at Waterstones Piccadilly on Wednesday evening. More details on his website. You can pick up Iconicon here.

News bits

Following the murder of 19-year-old student Sabita Thanwani in Clerkenwell on Saturday, police arrested Maher Maaroufe on Sunday afternoon. Maaroufe was thought to have been in a relationship with Thanwani and was with her on the night she died.

Hundreds of protesters gathered outside Stoke Newington police station on Friday afternoon in solidarity with the Black teenager who was strip-searched by officers while on her period. Then, on Saturday, a crowd of thousands marched on Whitehall “demanding an end to racial discrimination”.

Meanwhile, the Met has chosen to appeal against the ruling that it breached the rights of Reclaim These Streets over their planned vigil for Sarah Everard. The Met said over the weekend that it had “taken time to consider” the ruling and wants to “resolve what's required by law when policing protests and events”.

A few weeks ago we wrote a whole issue about how financially entangled the current government is with the oligarchs of London. On Saturday the Times broke the story that Boris Johnson was at a Conservative Party fundraising dinner in central London “attended by at least one donor with links to Russia,” on the night Vladimir Putin launched his war in Ukraine.

Getting back to the Dome for a second. The section of the O2 that’s been closed since Storm Eunice ripped the roof last month, has reopened. Although one small part is still closed as “work continues to fix a hole in the roof”.

The Guardian has weighed up the chances of Uber’s London licence being renewed this week. They also note that, even if the licence isn’t renewed then the company will still be able to operate pending appeals.

The average rent of a single room in east and west of central London has topped £1,000 per month for the first time, after prices rose 26% in the past year. Renting in south London increased by 10% to £758, east London rose 14% to £766, and north London increased 11% to £755.

A couple of contrasting art stories to finish off. First off, Damien Hirst’s 18-metre-high, bronze, headless sculpture ‘Demon with Bowl’ is going to be installed on the Greenwich Peninsula, next to the cable car (planning permission willing). While, on a slightly different scale, the Guardian has profiled the work of artist Raphael Vangelis whose Brickflat street art series “reflects the cramped living conditions many endure” living in London.