Niall Kishtany’s new book The Infinite City attempts to place London “as the capital of utopian thought,” which might come as a surprise to some people, especially if you consider one view of utopia is a “place or state of things in which everything is perfect”.

Despite this apparent contradiction, Kishtany’s book has already picked up glowing reviews from Literary Review and The Telegraph, the latter of which described The Infinite City as “bravely challenging those who view London merely as an infernal maze, as a centre of wealth, power and empire”.

Well, we’ve definitely been guilty of painting London as some of those things in the past, so - never ones to shy away from a challenge - we got Niall on a Zoom call to talk to him about why London tends to produce visionaries and social prophets, how various characters have gone about trying to transform London over the centuries, and how much optimism and scope there is for visionary thinking in the London of 2023.

Before we get into today’s issue, just a reminder that our Monday editions are completely free to read, but if you enjoy London in Bits then you might consider becoming a LiB supporter for £5 a month or £50 a year. The only reason we don’t have to run adverts or take money from sponsors is because hundreds of people choose to support what we’re doing.

If you become a subscriber then you’ll start getting our Wednesday issues as well as access to the entire back catalogue of paywalled articles, including our growing ‘Before You Go’ series, in which we visit some of London’s most beloved but endangered spots; and our ‘Electric Theatre’ series, where a different contributor writes about one of their favourite examples of London on film every month.

Hi Niall. Before we get into talking about the book we need to ask you the same question we ask everyone, which is ‘What’s your relationship to London?’.

I’m a born and bred Londoner. I was born and brought up in Wimbledon. My dad is from Iraq and my mum is from Cornwall, but they were both pulled to London because of its culture and that promise of the ‘London life’ I suppose.

I had a period in my twenties and thirties where I was working overseas in international development, but I’ve always gravitated back to London.

Your first book, A Little History of Economics, was really well received, but it didn’t have anything to do with London, so what made you want to write a whole book about utopian visions of the city?

The project of the book is to present an alternative story of the city that sits alongside these very dominant narratives: the city of wealth and power that’s the centre of empire and the centre of politics. I wanted to present a different thread; to try and recover a utopian heritage that I thought might be in there, and to try and crystallise that story.

I didn’t pick utopia just for the heck of it. I believe that utopia is a really important concept that has a lot to offer and I think that, as a society, we need to embrace utopian ideals.

There’s the concept of utopia and there’s the different ways we imagine London. This book puts those two things together to see how they enrich each other.

Can you just define utopia for us? Maybe explain how you would define it broadly, but also how some of the people you talk about in the book would define it. Because it means different things to different people, right?

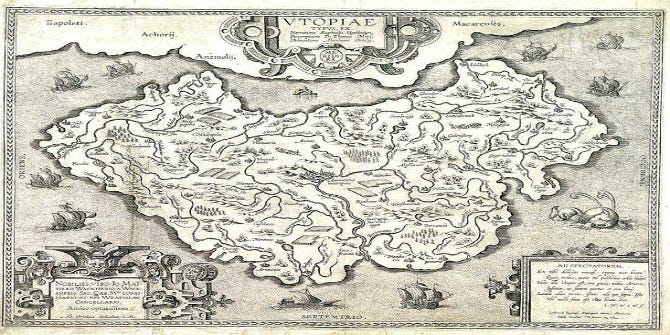

The word was coined by Thomas More who was obviously a Londoner but who was maybe more famous for his political activities and his falling out with Henry VIII. But early on in his career he wrote Utopia, which coined the term. It’s kind of a pun really, because it could mean ‘no place’ or it could mean ‘good place’. So you have this idea of the good but also negation. In other words, something good that is slightly beyond the horizon of the possible.

Then you’ve also got this element of the place, something more than just imagining on the basis of some abstract set of principles or philosophy. Typically a utopian will clothe these principles in a real story populated with actual people and set it in a real place. It’s that combination of the abstract and the concrete that I find really interesting,

In the book I use London as the frame for that place and each chapter is a little utopian tale happening within a slice of London. Even though London itself is somewhere that has often been considered a sort of dystopia or, at least, a foil to the dreams of utopians, that creates a sort of narrative energy that people have used as a way to imagine something better.

More didn’t set his utopia in London though did he, even though he was a Londoner?

No, More’s utopia was a classic island story, probably located in the New World somewhere. But what’s interesting about it is that the main city of Amaurot has got these strange echoes of London in terms of how the river flows and the bridge that spans the river. It feels like a reimagined London that has been morally and spiritually transformed.

So what are utopias for, if they’re more than just dreams?

There are different notions of utopia, but the picture that probably springs to mind for most people is a 19th Century man, probably with white hair, with some eccentric followers behind him, who is handing out pamphlets that say ‘This is my plan for the regeneration of humanity. If only you will listen to me, this will fix everything.’

That’s the sort of classic idea of the fixed utopia that creates absolute perfection. But what I get to later in the book is that sense of a much more performative and experimental utopia, that doesn’t have an all-encompassing blueprint, but is more about improvising in the moment and acting as a process for exploring our desires.

You talk about different types of utopians in the book, but the one everyone thinks about is that demagogue figure who has a grand philosophical vision and a band of followers, who does an awful lot of talking.

In the early 19th century in London you couldn’t move on the street for zealous social prophets because it’s one of the most utopian periods in history. It’s the first phase of industrial revolution, there’s massive change in London, it’s the end of the Napoleonic war, a depression is happening and the old structures are no longer working. So there’s this frenzy of debate about what to do next.

You've got all these utopian communities being set up in America, while in London every other person has got some tract which they claim is the solution to everything, and the archetype of that kind of person would be something like Robert Owen who was one of the first socialists. The words socialism really came from his idea of the social system and the idea that solutions have to be social rather than individual and cooperative rather than competitive.

He was very much an early example of a utopian prophet. He had this plan that he announced in 1817, at height of social unrest in London, to set up these social communities. Around him was this profusion of mini prophets who were inspired by him, and each one of them was peddling their own utopian system.

After that period though, a kind of disillusion sets in as people realise that utopia is not just around the corner and it’s a bit more complicated than that.

That leaves the other kind of utopian visionary, the one who is more concerned with shaping the environment around them. The ‘town planner’ style of person who wants to design their way to a better world.

I try and capture this tension in the book: that sometimes, the utopian dreaming that happens in London is slightly abstract because London is so big it’s like trying to design a world. But, at the same time, it’s also a place with localities and concrete things.

So you have people like Ada Salter who are trying to do concrete things in a particular locality, but those things are coming from more abstract principles and yearnings. And that's why I think you can call Ada Salter a utopian, because she had that bigger vision.

The relationship between politics and utopia is quite complicated. Some utopians want to turn away from politics because they feel it’s an irredeemable system that they can’t sully themselves with. But there are points in the book where they do come together and London from the early 20th century is one of those points, because these city political institutions develop that eventually lean leftward. So you get people like George Lansbury and also Ada Salter whose work is a great example of utopia and the political system joining up briefly in Bermondsey.

We’ve written before about Ada Salter and her impact on Bermondsey, some of which you can still see today. Are there other utopian remnants in London that are still standing?

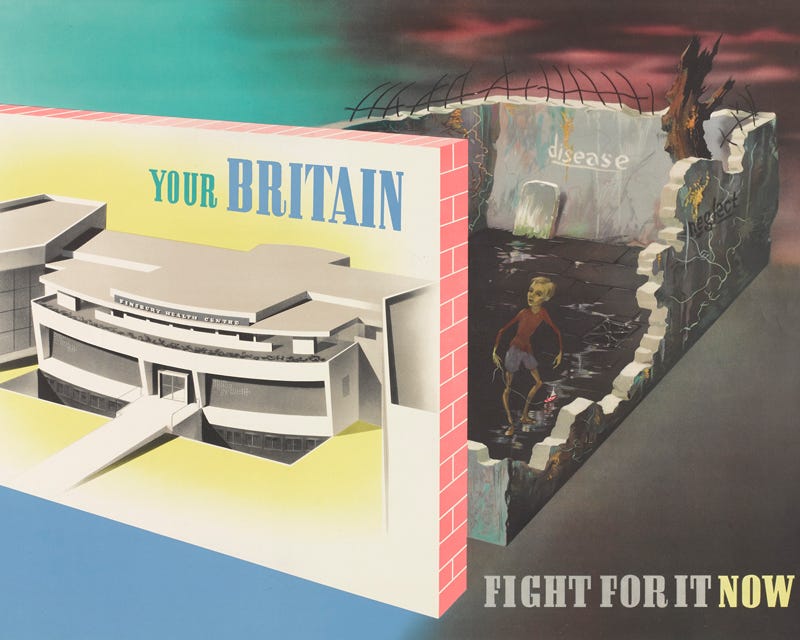

Alongside Ada Salter the other example of where politics and utopia come together is Berthold Lubetkin, the Russian socialist architect who was involved in rebuilding bits of Finsbury in the 1930s.

In the book I tell the story of the creation of the Spa Green Estate and the Finsbury Health Centre which prefigured the NHS. So there are definitely these tangible bits of utopian London that are still there. The Lansbury Estate in Canary Wharf is another example.

What about the 21st century? How relevant is utopian thinking in the London of 2023 would you say? And how optimistic are you about the future of utopianism?

Where I get to at the end of the book is the most recent utopian window that I think emerged during lockdown. Some of the later utopian movements in the book, the ones that are less about a blueprint and more about experimentation, they talk about the need to disrupt everyday life, which is an idea that was taken up by the Situationists and the psychogeographers, but during lockdown it almost happened by default. Because our daily lives were so disrupted there was lots of talk about not wanting to go back to the old normality, and a lot of people were suddenly reevaluating their lives.

The mid 20th century utopian theorist Ernst Bloch had the idea that these kinds of utopian yearnings are deeply embedded in society and they bubble up through the culture in all sorts of different ways. Not just by people who call themselves utopians presenting their visions, but also musicians and writers and artists who are just expressing a fundamental yearning that exists within society.

You see it it in what happened during COVID and you see it in some of the movements like Extinction Rebellion and Reclaim these Streets. It bubbles up even in the midst of what can feel like a very kind of anti-utopian time, and my book is saying that we need to embrace that and cherish it and take it seriously. We need to recognise that there is a utopian heritage out there that we can be inspired by and use to cultivate our own desires, and that's really essential for a healthy society.

So, yes, I am optimistic. We can’t just say ‘Oh, it’s too difficult’, because the whole notion of utopia is about finding possibility in impossibility and that's a very powerful creative force that we need to embrace.

The Infinite City: Utopian Dreams on the Streets of London is published on July 20th, You can order it via Harper Collins or via Bookshop.org.

There’s more about Niall here and he’s on Twitter at @niallkishtainy.

5 little bits

The Met has announced that, as well as the 7% pay rise that was announced on Thursday, its officers will also get an annual salary increase of £1,000 a year, to help it “recruit and retain the best people”.

Minister for London, Paul Scully has used the pages of The Telegraph to declare that “Susan Hall is the best candidate for London mayor”. However, most of the column is devoted to Paul letting us know how “gutted” he was not to have been shortlisted for the mayoral race; a decision that - he’s at pains to explain - came about because the “shortlisted candidates were specifically selected with less profile and political experience”.

The Telegraph has also had a look at how the City of London is planning to convert “old offices nobody wants” into hotels “as part of plans to turn the financial district into a ‘global leisure destination’”.

Footways, the social enterprise that “develops quiet and interesting routes for walking and turns them into beautiful maps” has created a map of the Camden Green Loop (the project that celebrates “the beautiful public spaces” across Camden Town, Euston and Kings Cross). The maps contains tips from local people and includes The British Boot Company, the Fiddler’s Elbow and (sticking with the theme of today’s issue) Oakshott Court.

Darren Hayman (up to now, best known as the lead singer of Hefner) has been painting the nighttime London he sees while walking his dog, and the resulting pictures have been collected into a book called The Last Dog Walk. There’s also an exhibition of the paintings launching on Thursday at the artdog gallery near Forest Hill.

tail – bony appendage to rear of creature eg dog, cat

pedal – use a cranked mechanism to create rotational motion eg bicycle

Nice story, but could you have slipped the divine Alison Goldfrapp in there by some sleight of hand?

London is a reactor where people and ideas collide in interesting ways. So are most metropolises but the English tolerance for eccentrics, oddballs, misfits and nonconformists yields more creativity than, say, more staid Paris.