Mapping London, from Brutalism to Birch trees

An interview with Blue Crow Media's Derek Lamberton

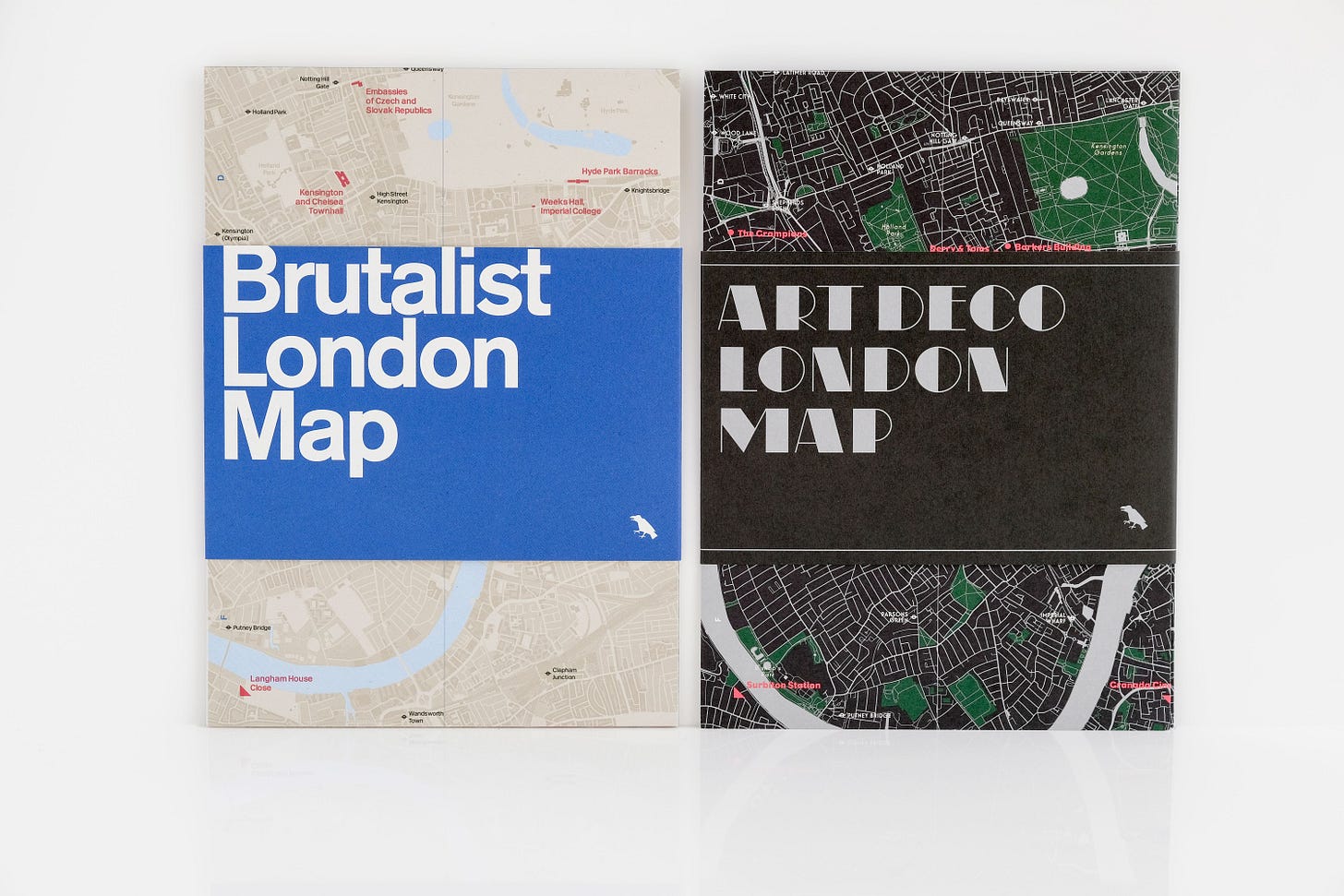

There are two independent publishers we consistently turn to go when we want to buy gifts for other Londoners. One is Cafe Royal Books, who publish incredible titles like Notting Hill Sound Systems and Spitalfields 1977. The other is Blue Crow Media who have been producing gorgeously designed and thoughtfully curated maps of London for the past seven years.

From the architecture of the Underground to the London of Nicholas Hawksmoor, Blue Crow has carved out a reputation as London’s trusted annotators, so we wanted to talk to founder Derek Lamberton to find out how he went from beer and coffee to Brutalism and back alleys and what it takes to run a small, independent publishing company in London in 2022.

Let’s start off with the usual LiB opening question: What’s your personal relationship to London?

Well, my mother is from London and her parents were Londoners, but I grew up in Washington DC and came here as a child to see my grandparents. The beginning of my real relationship with London was when I studied for a Master’s degree at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies in the early 2000s. I was living in UCL halls and naively assumed that if I stayed, I would live in Bloomsbury for the rest of my life!

How long did it take that for that dream to disappear?

Not long. When I was looking for my first flat, I realised I would have to pursue a line of work at odds with my interests and maybe skill set in order to make that possible. So obviously I’m not in Bloomsbury anymore. I live in Brockley now - maybe it will be the Bloomsbury of the 21st Century?

Can you tell us a little bit about how Blue Crow Media began and when and why you started producing the maps of London?

I worked as a journalist and for NGOs after my degree, living in Afghanistan, Russia, Bosnia and then back to the US, where I didn’t want to be. So I came back to London with a job at National Geographic, and subsequently at Current. I became interested in speciality coffee around then, and put together an iPhone app called ‘London’s Best Coffee’ with a developer friend. The app was popular with a niche audience, and I published a few more similar apps including ‘Craft Beer London’. The apps did well, although it was a limited market.

So what prompted the move from digital to hardcopy? Especially as most people were going the other way?

Developing apps just wasn’t a very nice way to make a living. It required a lot of customer service (people were downloading apps for the first time and would write asking how to do it!), and the apps needed to be updated constantly. The price point for the apps was too low to maintain, and the customer potential was too limited. It was frustrating because the product was good.

At that time I was working in a shared office space on Scrutton Street, working next to a book designer. The two of us were eating lunch one day and — I must have been complaining about things — we cooked up this plan to take the content from the coffee app and to produce a paper map with it.

We started making these small pocket-size maps, and the coffee shops started selling them, and that was that. It was a much simpler business model. That led to the Brutalist London Map, which was the first architecture guide. Originally I was going to do that as an iPhone app, but the 60s-70s design aesthetic made much more sense on paper. The map did well. It seemed to hit at the right time and it allowed me to drop the apps and shift into a more successful business model — albeit one that hasn’t resulted in an office in Bloomsbury!

Was that when you decided to leave coffee and beer behind and make architecture your niche?

Architecture has always been an interest of mine, but in terms of publishing it was an unexpected niche to end up in. The maps worked, and continue to, because they are affordable, where many architecture books are not. Despite the modest price, we seek to produce high quality publications: I’ve commissioned experts for each title, and original photography. We use very nice paper, and I like to think they’re nicely designed.

But the trajectory has been an odd one in terms of the business and it can be challenging because beyond the design, it’s just me and I don’t have an expertise in print publishing. I’ve had to figure it out for the most part. I’ve been very lucky that people I’ve met here and there, even on Twitter, have been very generous to talk to me about publishing and how marketing works etc, which has been really helpful. But it continues to be a learning process.

How challenging is it to update the maps, especially as so many of these buildings seem to be in constant danger of disappearing?

The Brutalist map, edited by Henrietta Billings, originally came out in 2015, and we’ve just released a second edition recognising buildings that have been destroyed since then. The 20th Century Society, where Henrietta worked at the time, has also been involved. If Brutalist architecture is going to survive in London it is largely thanks to them.

But Brutalism is, and never will, have popular appeal. The benefit of this, if there is one, is that those who do like it, really engage with it, and are often vocal about it. But we’ll see what happens over the next generation. It seems like we’re entering a stage now where concrete is starting to become unpopular for sustainability reasons, and it will be interesting to see what the reaction is to that. To demolish them and replace them with something else is ludicrous in terms of sustainability, but how often has sensibility been the driving force in this picture?

It will be intriguing to compare the discussion around it to the buildings on our Art Deco London Map where everything is preserved or restored and firewalled from developers — regardless of the materials.

That seems like a good segue into the question about what prompted the change in direction from maps about concrete to maps about nature and the Great Trees of London Map that came out a couple of years ago.

Creating that map was a lot of fun, although there were challenges. If you’re making a map of Brutalist buildings in London, there are, say, 70 to 100 buildings that can be classified as Brutalist, and then about 50-60 of those that are actually of significant interest. But to select 50 trees in London that you can identify as ’the most interesting’ for a variety of reasons? That’s a hell of a challenge. The editor, Paul Wood, was a lot of fun to work with and the map turned out well.

It came out just prior to the pandemic, and there were a lot of people gifting it to one another in lockdown. People were giving it to their parents or their grandparents or their grandchildren, so they could could go out and figure out where their local trees are. It felt like we had produced something that was bringing genuine happiness to people.

That map really tapped into that lockdown phenomenon of people going out and rediscovering their immediate surrounding and making the most of that ‘one hour’s exercise a day’. Also, I had no idea you could find things like a Giant Redwood in New Cross!

Paul has put together a remarkable way of life: researching and walking around cities and identifying interesting trees. He is a proper street tree expert. And he recognised that the way to reach people was to put street trees like the Redwood growing next to the tracks at New Cross Gate Station on the same level as the well cared-for and known trees in Kew Gardens or Hyde Park. Regardless of where they have grown, these are Londoners’ trees and we’re responsible for caring for them and celebrating them.

The trees map seems to have opened up new avenues for you that aren’t all about architecture.

Absolutely. We have a map that just came out called the London Alleyways Map that’s written by [previous LiB contributor] Matthew Turner. And then coming up we have a London Street Signs Map, a map of the typography of Hackney, and also a map of Black History of London.

We’re not moving away from architecture, we have a Modern Lisbon Map coming up and one on Brutalist architecture in Buenos Aires. But we want to (and have to) try new things and the benefit of being a tiny business is that I can take chances here and there, even if a title isn’t successful.

Obviously, printing costs are such that I can’t get it too wrong, but some titles are more popular than others. I’ve made it seven years producing these maps, so if I can get another seven years then that would be great! Even if Bloomsbury is off the cards.

Take a look at all Blue Crow’s London maps here.

We’ve already grabbed a copy of the new London Alleyways Map by Matthew Turner and it’s a thing of beauty.

And if you’re into your maps or just walking round London, Footways just released a new edition of their map of quiet routes through Central London. You can pick that up for free at Network Rail stations.