Welcome to the jungle (aka Wardour Street)

An exclusive extract from 'Marquee: The Story of the World’s Greatest Music Venue'

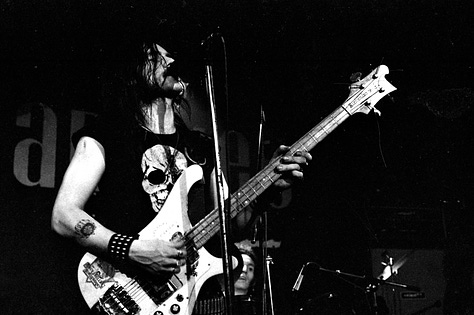

‘The reason I liked the Marquee was because it was scruffy and a hellhole, and your feet stuck to the floor, and that’s exactly what a rock and roll club should be like.’ - Lemmy

That’s the quote that opens Marquee: The Story of the World’s Greatest Music Venue, the new book from publishers Paradise Road (out today). And it’s a view endorsed by Robert Sellers, who wrote the book with the help of Nick Pendleton, the son of Harold and Barbara, the Marquee’s original owners.

“In the cold light of day, when the lights were on, it was pretty shit,” Sellers laughs. “But when the lights went off and it was full of people, the Marquee just became magic. It had this special atmosphere which meant that when the spotlights were on and the crowds were in, it became this amazing place.”

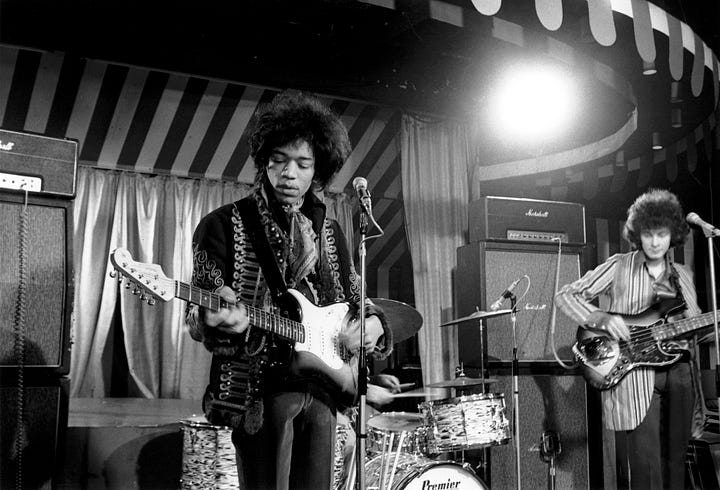

That claim is borne out by the list of iconic acts that played the Marquee over the years. What began life in 1964 as a jazz club quickly transformed into what Seller’s describes as “a place where people went to see good music of any type” and that openness to all genres and movements (from blues to ska, via punk and prog) meant that it attracted a huge range of bands, many of who would go on to be giant, stadium-filling acts.

The Rolling Stones, Bowie, The Who, Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, the Sex Pistols, the Stranglers, the Jam, the Police, U2, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, ZZ Top, Faith No More, Guns N’Roses, INXS, Metallica, Queen, REM… They all played that, scruffy, sticky-floored room on Wardour Street; mostly as they were on their way up.

“It was a ‘first rung on the ladder’ sort of place,” says Sellers. “You might have been playing small clubs and the back rooms of pubs, but if you played the Marquee that meant you were on your way and the next stop was probably the Rainbow and then the Hammersmith Odeon. After that, it was Wembley.”

Because it played such a crucial part in so many careers, the Marquee still holds a special place in the memories and hearts of a lot of artists, and that meant Sellers had no trouble extracting plenty of stories from those who graced its stage over the years.

“It meant a lot to them, so a lot of people were so happy to talk about those days,” he says. “They talked about turning up on Richmond Mews in their vans, driving down that tiny road behind Wardour Street and unloading all their equipment. I must have interviewed about 50 or 60 musicians who played there, and my worry was that they were all going to have the same stories and give me identical quotes. But they all had their own take on the place. They all had their own set of very funny stories.”

The book is structured around those stories, with around 60 sections that run chronologically from the mid-60s through to the late 80s, with a short epilogue for the 90s, when the club moved to Charing Cross Road. Each of these mini eras is captured through the adventures and misadventures of the people who ran the place, played it or were in the audience.

“Keith Moon was a regular visitor,” Sellers grins, “and he came in once with a dead fish on a dog lead. It was a pike or a trout or something. A big fish. He went to the cloakroom and left it there. Got a ticket for it and everything. Never collected it.”

Sellers explains that, because the club didn’t have a bar for the first six or seven years, most people would go for a drink in The Ship on Wardour Street before a gig. “You could bump into anybody in there,” he tells me. “I spoke to Johnny Warman of the band Bearded Lady and he told me that he was in The Ship once, and there was a guy in there dressed in a huge black cloak with these bat-like wings. When he turned around he saw that it was Freddie Mercury having a drink before Queen played that night.”

It seems some legends were easier to bump into than others.

“If you were are at the Marquee you had a one in ten chance of spotting Lemmy,” Sellers laughs. “He was there all the time, propping up the bar. He did a Jeffrey Bernard once and got locked in. U2’s roadies turned up one morning and found him in there, awake and playing the Space Invaders machine. He even offered to help them load in their gear!”

Below we’ve got an extract from Marquee: The Story of the World’s Greatest Music Venue, which tells the story of when Guns N’ Roses played their first European gig at the club in 1987.

You can buy the book directly from Paradise Road here.

While you’re there check out their other books, like Peter Watt’s Up In Smoke -The Failed Dreams of Battersea Power Station and Nick Hunt’s The Parakeeting of London: An Adventure in Gonzo Ornithology.

Welcome to the Jungle

‘It’s good to be in fuckin’ England, finally!’ shouts Axl Rose as Guns N’ Roses take to the stage and immediately kick into opening number ‘Reckless Life’. It’s Friday 19 June 1987 at the Marquee, and it’s the band’s first gig in Europe – almost their first gig outside of their home base of Los Angeles. A roar of applause greets the end of the first song and, before it dies down, Slash’s fuzzy sheet-metal guitar kicks into ‘Out Ta Get Me’. It’s all looking good – until the first can of beer whistles by Rose’s head.

Over the previous two years, GN’R had been working the West Coast rock scene, one among a host of flash bands with radical hair and a 1970s album collection. It was their manager Alan Niven’s idea to fly the band to the UK in the hope of creating a media buzz that would give them some credibility back home. Niven knew about the Marquee, knew that it was where the Rolling Stones and the Sex Pistols had played – Exile on Main Street and Never Mind the Bollocks were GN’R favourites. He thought it wouldn’t hurt to have his band linked with bands like those.

In advance of their transatlantic jaunt, the band’s label, Geffen, had flown a bunch of UK music writers out to see GN’R live in LA, so when the band arrived in London there was already a buzz building. The five band members – Rose, Slash, Izzy Stradlin, Duff McKagan and Steven Adler – spent the week leading up to the gigs rehearsing at a rental studio, and otherwise hanging around Soho, shopping for clothes, getting drunk and picking up girls. The Marquee’s manager, Ian ‘Bush’ Telfer, had been warned that the band’s performances were so incendiary that on occasion they exploded into riots. ‘They ended up being the nicest bunch of blokes,’ says Bush. ‘I had to tell Axl to stop calling me sir.’

Before the first show, Niven sat the band down for a pep talk. Listen, he said, they’re going to look at you like a bunch of LA wankers. They’re going to test you. They’re going to yell at you. They’re going to spit at you. And if you blink, you’re dead. You give as much as you get.

Which may be why Axl Rose’s response to that first thrown can is to scream, ‘Hey! If you wanna keep throwing things, we’re gonna fuckin’ leave. Whaddaya think?’ Another missile crashes into the drum kit.

‘Hey!’ Axl screams. ‘Fuck you, pussy!’ Clearly rattled, the band continues on with ‘Anything Goes’. They perform eight of the twelve tracks on their soon to be released debut album, Appetite for Destruction. The missile throwing stops but there is plenty of heckling between songs. GN’R close out the show with Aerosmith’s ‘Mama Kin’, introduced as a song they play ‘better than the other fuckers’. As the band leaves the stage, Slash invites the crowd to a drink at the bar.

‘They came off drained,’ recalls Bush. ‘I came backstage and Axl was collapsed on the floor of the dressing room and Slash was being sick in the sink. The crowd were baying for more, and I told them to get back on stage. They did another couple of numbers, came back off again and they couldn’t even talk.’ A journalist for the heavy rock fortnightly Kerrang! was not impressed. He thought the band had bottled it, rattled by some thrown beer cans.

The second Marquee show was three nights later, on 22 June. The support band that night was Little Angels, a rock outfit from Scarborough. Keyboard player Jimmy Dickinson remembers arriving early for the gig and catching Slash soundchecking on stage. ‘He’s literally got a cigarette in his gob, he’s got his top hat on, he’s stripped to the waist and he’s playing his Les Paul down by his knees with his ear up against an enormous speaker going, “I can’t hear my fucking guitar.” I literally couldn’t stay in the room because it was so loud. I was seventeen and it just blew my mind.’ Dickinson watched the Guns N’ Roses set from the bar. ‘It was unbelievably exciting. There was something in the air, you could smell it, this electricity, and you just knew they were going to take over the world from that one tiny show.’

During their stay in the UK there were numerous reports of the destruction wrought, particularly on their accommodations, but the band seemed to have nothing but respect for the Marquee. ‘Nothing untoward went on,’ says Bush. ‘They were only too happy to get a case of beer as a little present at the end of each night.’ Their sole mark on the place was made on the night of their third and final gig, on 28 June, when the band added a scrawl on a dressing room wall that read ‘Guns N’ Roses, a way of life’. But there was already so much graffiti on the wall that the new addition was hardly noticeable.

Four months later, GN’R were back in London, walking off stage having performed to a packed Hammersmith Odeon, and well on their way to becoming the biggest rock band in the world. By early January of the following year, Appetite for Destruction had sold a quarter of a million copies in the US and would eventually reach No.1 on the Billboard chart. But, as band manager Alan Niven said, ‘It was in Britain that we first generated a buzz’. Just another band blasted to stardom from the modestly sized launch pad of the Marquee stage.