This is a paid-subscriber only edition of LiB. If you’re receiving this as a full issue then thank you very much for supporting independent writing about London. If you’re not a subscriber already and you want to read the full thing, please subscribe for £5/month or £50/year:

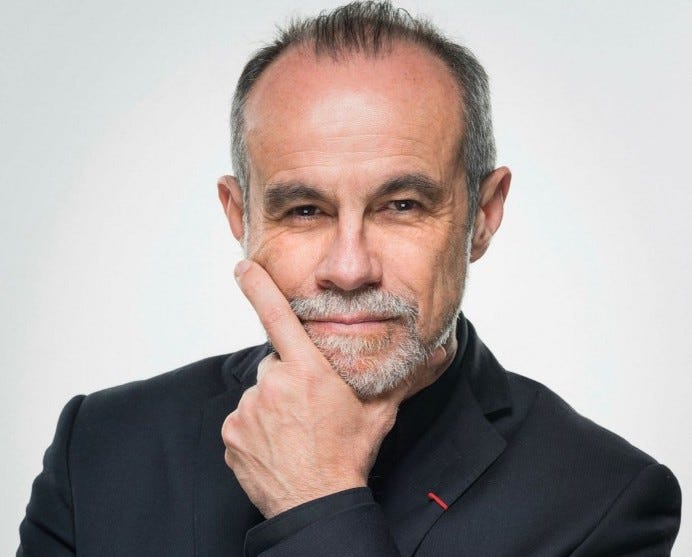

Last week, the French-Colombian scientist (and world class smoulderer) Carlos Moreno (below) won the third ever Obel Award. That’s the award given by the Henrik Frode Obel Foundation to celebrate “outstanding architectural contributions to human development”.

(It’s worth just taking a quick break here to explain that Henrik Obel was a Danish businessman who made a lot of money from his Spanish pest control business and then dedicated his entire fortune to establish a foundation “to reward exceptional works of architecture.” He also looked pretty great smoking a pipe.)

But let’s get back to Carlos. Carlos won the 2021 Obel award because, this year, the competition focused on “solutions to the challenges faced by cities around the world” and Carlos is the guy who came up with the whole concept of the ‘fifteen minute city’.

So, what is the fifteen minute city?

Very basically, the idea behind the fifteen minute city (or the “la ville du quart d’heure” as Carlos might put it as he pours you another glass of red wine while staring intently into your eyes) is that the urban essentials (where you live, work and shop, plus healthcare, education and entertainment) should all be a quarter-of-an-hour away from each other, either by foot or by bike.

Post-lockdown, all this might sound relatively obvious, but Moreno’s genius was coming up with the whole thing back in 2016 (although other people has proposed similar models before) and then teaming up with the Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, to make the concept a key part of her reelection campaign.

Their partnership has already been pretty productive. As well as getting reelected, Hidalgo has introduced the “Paris Respire” project, which closes some quartiers to traffic on Sundays and public holidays, turned miles of road into cycle-friendly “corona pistes”, added social housing to wealthier neighbourhoods, and turned school grounds into gardens.

It’s not just Paris which has taken the fifteen minute city idea to heart. Buenos Aires has introduced free bike rental schemes and Amsterdam has something called the City Doughnut (which we’ve read about but definitely do not pretend to entirely understand).

Can London become a 15 minute city?

At the end of 2020 the design and architectural firm, Arup surveyed 5,000 people from across London, Paris, Madrid, Berlin and Milan to try and assess the ‘liveability’ of each city based on Moreno’s ideas. What they found was that residents of Milan and Madrid were already able to reach their local amenities in under fifteen minutes, while those in Paris and Berlin were around the sixteen minute mark. But London was lagging behind. It turns out we are a twenty-three-and-a-half minute city at best. Plus, we “had by far the largest number of people (59%) who considered leaving and the highest (41%) that moved out temporarily. Almost half of Londoners complained that amenities were too far away.”

On the basis of just that evidence it seems that the idea of creating fifteen minute neighbourhoods is at least something London should be exploring. Plus, the pandemic has done a lot of the hard work in terms of convincing people that remote working can be productive, as well as reminding everyone of the of the benefits of their local area.

And we’re already doing it… Kind of.

At the end of last year the campaign group London Living Streets produced a report that identified a network of 200 “town centres and high streets across London around which we can create a highly sustainable city” (although, judging by colour scheme of this PDF, we’re not sure we’d trust them to design an entire neighbourhood).

They focused in on Walworth Road in Southwark, which they said had the density of people, low car ownership levels , access to amenities, pedestrian friendly high street and the right amount of green spaces to qualify as a fifteen minute neighbourhood.

A couple of months later the Wall Street Journal was declaring the Brent Cross Town development (due in 2024) as a fifteen minute neighbourhood thanks to the planned “3 million square feet of office space and about 50 acres of parks and playing fields” the area would contain, as well as “stores, restaurants, a movie theatre and three schools.”

If you believe the ‘build-to-rent’ company Vertus, the Wood Wharf on the Canary Wharf Estate makes the fifteen minute city idea a “firm reality” because it lets you “switch seamlessly from boardroom to boardwalk, and from beauty treatment to delicious dining experiences.”

It’s that kind of PR drivel that highlights what happens when Moreno’s ideas get clumsily adopted by marketing teams and estate agents who think they can use them to paper over a lack of genuine social integration and community development.

The O2 has been put forward as a 15 minute city enabler because it “has become a gathering place to live, work and celebrate.” And even the Nine Elms development has been touted as the “archetype of the 15-minute city concept,” but that’s only true if you measure it by how close some stuff is to other stuff. As we’ve already established that area is an ugly, soulless hole where “cars are more important than people” and which “offers little in the way of cafes, restaurants and entertainment.” That doesn’t sound like the utopian vision offered up by Mr Moreno, and we feel like Henrik Obel would choke on his pipe if he accidentally stumbled on the Vauxhall and Nine Elms development.

Elizabeth Uviebinené probably put it best when she wrote a piece for the Standard back in May, in which she said:

“The 15-minute city needs to work for everyone and this is best achieved by a combination of local investment, community engagement and government initiatives.”

Uviebinené called out the East Bank project in the Olympic park and the Meridian Water development in Tottenham as good examples of where investment from the mayor’s office, government and private companies had combined to create “a focus on new jobs, lifelong learning and entrepreneurial opportunities for local people,” as well as“community facilities, social enterprise hubs and affordable homes earmarked for ‘makers and creatives’”.

What’s the downside?

As lockdown restrictions have eased over the past few months we’ve seen a bit of a fifteen minute city backlash prompted by a desire for London to be ‘connected’ and ‘alive’ again. In May Edward Glaeser of Harvard wrote an article for the LSE that praised a lot of the aspects of the fifteen minute concept… just not the fifteen minute bit:

“The basic concept of a 15-minute city is not really a city at all. It’s an enclave — a ghetto – a subdivision. All cities should be archipelagos of neighbourhoods, but these neighbourhoods must be connected. Cities should be machines for connecting humans – rich and poor, black and white, young and old. Otherwise, they fail in their most basic mission and they fail to be places of opportunity.”

Glaeser’s urging that we should “bury the idea of a city that is chopped up into 15-minute bits” and instead “embrace the idea of the whole city that is connected with the whole of our metropole and with the whole of the world,” is echoed by Anthony Breach, from the Centre for Cities, who told the FT that the fifteen minute principle “would go against the grain of what we know about city life. Workers want to work in places where land values are high, and live in a place where land value is cheaper.”

In March, London-based writer Feargus O'Sullivan wrote a piece for Bloomberg which cautioned against the fifteen minute city on the grounds that it could “further alienate marginalised communities” by failing to address the “deep social divisions” our existing city structures have created. The article quotes the Toronto-based urban designer Jay Pitter:

“What we see already within marginalised communities is resistance to things that are actually really wonderful and beneficial, like more walkability or bike lanes. The reason we see this resistance is because these kinds of approaches, while good for us and the environment, also often spur gentrification. And so communities are very nervous about that.”

Which is a pretty depressing reality, but a reality all the same.

That point of view is taken to its ridiculous nadir by Rob Lyons, writing in the Telegraph who uses the idea of the fifteen minute city to beat up on the idea of low traffic neighbourhoods, green traffic measures and cycle lanes in general:

“This sort of thing might appeal to urban creatives who can cycle along to their local co-working space and crack open their Macbooks while enjoying filter coffee on tap. But the consequences of the 15-minute city for everyone else would be disastrous.”

Where does that leave us?

The mayor’s London Recovery Board does have a stated ‘mission’ to create High Streets For All; that is “thriving, inclusive and resilient” high streets and town centres that are “within easy reach of all Londoners”. All things that Carlos would no doubt approve of.

The biggest initiative to come out of that so far is the High Streets For All Challenge which has given £20,000 of seed funding to 35 project across London “aimed at ensuring our high streets can flourish and thrive as we emerge from the pandemic.” If you want to see if there’s a project in your area that’s benefiting from the Challenge, there’s a full list of them on this page.

There are of course, more high profile initiatives such as the ULEZ expansion and Low Traffic Neighbourhoods that are changing the way we navigate London, but which are also, for the most part, still being assessed and are incredibly divisive, as any “top-down technocratic, urban planning” (to quote that Bloomberg article again) is bound to be.

In the end, not having to leave your local area doesn’t mean you won’t want to every now and again. Central London is already shifting away from being a necessary daily trip, to becoming a more occasional indulgent ‘experience’, and that’s not a bad thing for our wallets, our local communities, or our environments.

But as Nick Bowes said in our Monday issue, real change will only come when communities are empowered to make local decisions. “Meaningful devolution” should mean those worries of gentrification-by-stealth and top-down technocrats are less likely to occur and the people who live and work in an area can take some of that energy and empathy that was forged during lockdown and harness it to breathe new life into London’s neighbourhoods.

After all, London will always be more than the sum of its parts, but we’re really at our best when those parts are really humming.

And the rest

Two Met Police officers have admitted to “taking and sharing photographs of the bodies” of Bibaa Henry and Nicole Smallman. The officers “breached a cordon to take ‘inappropriate’ pictures of the bodies, which were then shared on WhatsApp.”

TfL has asked its consultants to begin working up “detailed tunnel designs” for the Bakerloo line extension. The £3.1bn scheme (which would extend the the line from Elephant & Castle on to Lewisham) had been put on “indefinite pause” (because TfL has no money), but now it looks like TfL are working with Southwark and Lewisham to raise funds.

The Guardian reports on how traditional black cabs are ‘cashing in’ on the fact that Uber, Bolt etc are becoming harder to find and more expensive.

The TV presenter Hannah Fry resigned as a trustee of the Science Museum last week after the museum signed a sponsorship deal with the fossil fuel company Adani.

Two houses with very different ‘cultural importance’ came on the market this week. Herman Melville’s Grade II Listed Georgian house on Craven Street can be yours for £4,500 per week. Or (if you’re old enough to remember it) maybe you want to go for the six-bedroom ‘Big Breakfast house’ on the edge of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, which has just gone on sale for £4.6 million.

By 2024 it should be possible to fly from Rotterdam to London in “an airplane that runs entirely on hydrogen with zero carbon emissions”.

To mark the release of Last Night In Soho, the NME has put together a music lover’s guide to Soho.