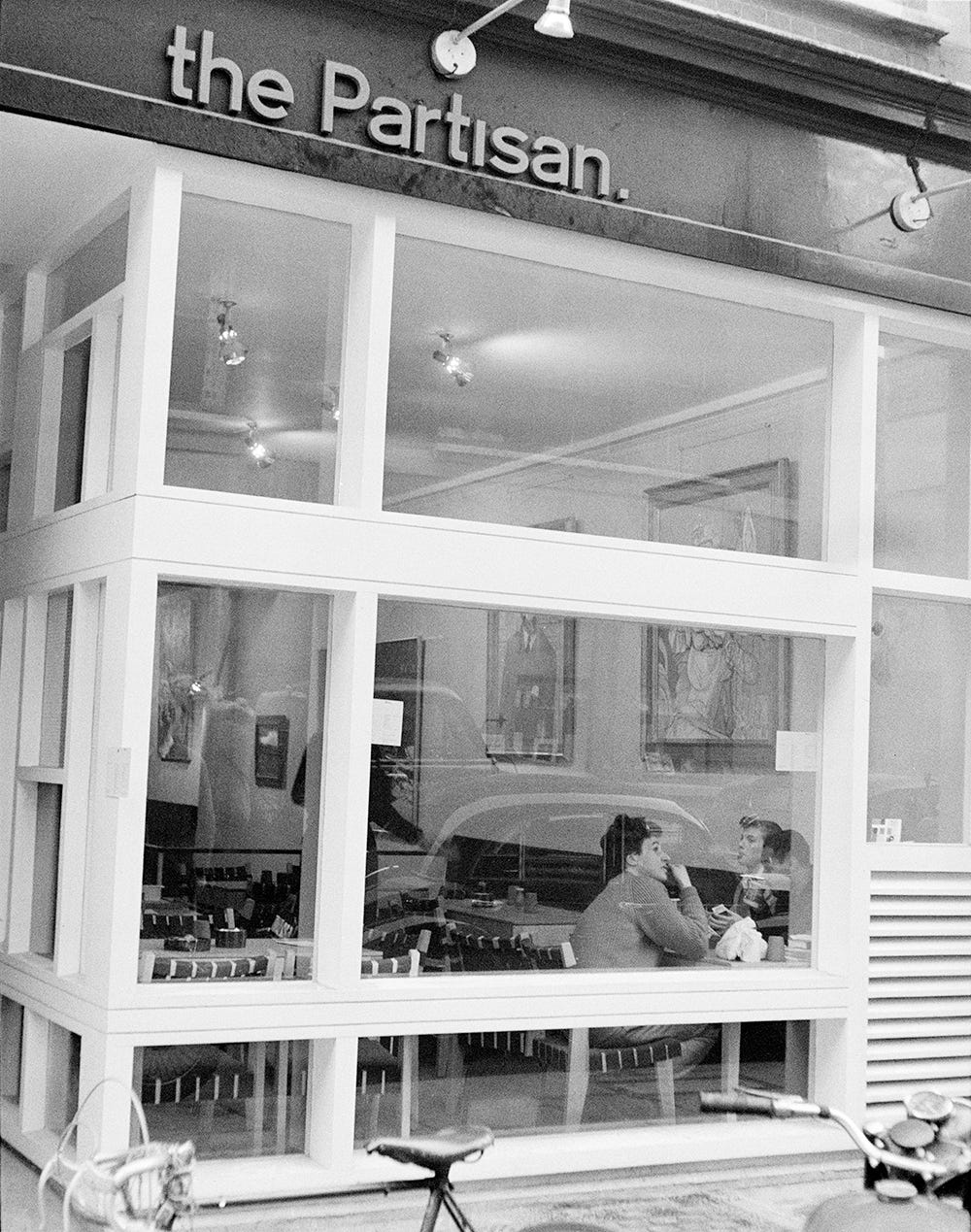

If you go along to the Photographer’s Gallery over the next few weeks and go up to the third floor, you’ll find a single room with a chessboard in its centre and a selection of black and white images of young men and women on the walls.

The subjects of these photographs are young, most of them are in their early 20s. But even though these photos were taken at the dawn of the 60s, this is not ‘swinging London’. There are no mini skirts or mod suits, just sensible knitwear, jackets and ties.

These were all customers of the Partisan, a short-lived but incredibly influential coffee house that uses to stand on Carlisle Street (right next door to where Private Eye’s offices are now). By all accounts the Partisan sold seriously mediocre coffee but it was also the epicentre of what has since become known as the British New Left.

“The New Left was the name that came to be used to describe this movement that starts really around 1956 in the aftermath of the Suez crisis,” says Michael Berlin, the historian who has curated The Partisan Coffee House: Radical Soho and the New Left. “At the same time the Soviet Union invaded Hungary and crushed a revolution. In the wake of these two events you get the New Left, which was questioning the received wisdom about what it was to be a socialist. It was rejecting that Stalinist Communist Party version of the left, but it was also quite critical of some of the more mainstream aspects of the Labour Party, which it saw as being a soggy compromise.”

If you’re thinking that some of this sounds strangely familiar, then the domestic preoccupations of the group also have some resonance for anyone looking at the photos from the perspective of 2022.

“They were very critical of the proposals to knock down whole parts of central London and build huge commercial developments,” says Berlin. “They were interested in what was going on in the ‘New Towns’ that had been built in the 1950s, and whether or not they were genuine new communities or soulless places lacking any kind of sense of identity. And they were really engaged with the politics of anti-racism in Notting Hill and elsewhere.”

But this was no bunch of poe-faced, earnest academics. The images in the exhibition show smiling, energetic faces and impassioned conversations over cigarettes and coffee and the odd game of chess. As well as rewriting what it meant to be a socialist, the New Left were also having a good time.

“At the time that the coffee house was founded it was right at the heart of the espresso bar boom,” explains Berlin. “The Partisan set itself up in playful opposition to that by calling itself an ‘anti-espresso bar’. They would have seen places like Bar Italia as being crassly commercial and they saw themselves as being a place for people to sit and talk and contemplate political issues, have deep cultural conversations and play chess.”

According to Berlin, the menu at the Partisan could be as radical as the politics. “Raphael Samuel, was from an East End, Jewish background and he was what you might call a proto-foodie,” he laughs. “So there were things on the menu like Whitechapel Cheesecake, but there were also dishes like ‘Boiled Breconshire Mutton with Caper Sauce’ alongside Vienna sausages and chilli con carne, which was then considered quite exotic. But when I spoke Stuart Hall he said that the coffee wasn’t very good and people would nip across the road to get a good espresso from an Italian espresso bar.”

The radical heart of London

The photographs that make up this exhibition were all taken by the legendary photographer Roger Mayne (most well known for his iconic images of Southam Street, taken in the late 50s), and come from the archive of the historian Rafael Samuel, one of the founders of the Partisan alongside fellow historian Eric Hobsbawm and Jamaican-born sociologist, Stuart Hall. Between them, says Berlin, they had a “romanticised vision of the older type of coffee house of the continent. Of revolutionaries plotting in the coffee houses of Vienna.”

At that time, Soho was the obvious place to build that vision.

“You have to remember that Soho was historically a place for radical exiles, going right back to the European revolutions of 1848, when Karl Marx came to Soho as a political exile,” says Berlin.

“At the end of 19th and into 20th Century there were socialist and anarchists communities in Soho. There were French Communards and Italian anarchists and there were clubs and restaurants that they would use as meeting places. That tradition carried into the 20th century and it created some very famous locations like the delicatessen on Old Compton Street, called King Bomba, which was run by a multi-generational Italian, anarchist family.

“In addition to that, there’s the folk scene which is another aspect of Soho musical history that tends to be forgotten about. There were a lot of small, basement folk clubs. Places like Bunjies and Sam Widges that were all around Soho Square, very close to Carlisle Street. The folk scene was the cultural background to the anti-nuke movement and CND. So, there was a definite scene of radical culture that the coffee house was a part of.”

Demonstrating, debating and dancing

What this exhibition captures so brilliantly is the idea that young people in London could be openly politically and culturally engaged without feeling like they had to enforce strict agendas or build defensive, factional walls around themselves.

“The politics of it are really refreshing to look at from a 21st century perspective,” says Berlin. “There’s an open-mindedness and a broad, Humanist internationalism. It’s not sectarian and it’s not interested in small arguments between groups or whether or not you adhere to some kind of rigid party rule book. It’s open-minded and self-directed. The New Left was a broad church. I think today a lot of people are turned off politics precisely because of that kind of narrow mindedness that you often get in interactions between political groups.”

It’s certainly true that Mayne’s images capture that sense of sociability and camaraderie that only occurs when people get together to drink far too much bad coffee and talk about changing the world.

As Berlin describes it, “You can see that in the space they created. The idea that, as well as taking the world seriously, engaging in criticism and organising protest, you also had a right to enjoy yourself and dance and experience life!”

Closing time

The Partisan was deemed to be so influential that (it’s alleged) the Met had undercover operatives placed in the coffee shop to keep tabs on what the young radicals were discussing.

“People like Eric Hobsbawm and the novelist Doris Lessing were both involved with the project” Says Berlin, “and the security services were absolutely interested in them But it’s also said that Special Branch had two people going in there under the guise of playing chess. Although, I’m not really sure why anyone would want to eavesdrop on a conversation about town planning.”

Despite its growing importance, the Partisan’s ‘unusual’ approach to business eventually caught up with it and after just five years the coffee shop had to close its doors. But the New Left didn’t disappear with it. Indeed, many of its brightest stars went on to great things.

Raphael Samuel and Stuart Hall founded the History Workshop movement and the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies respectively. Typographer Desmond Jeffrey, who printed the Partisan’s opening invitations and menus, went onto become one of the most celebrated typographers of the last century; while graphic artist Germano Facetti, responsible for the beautiful designs that graced the pages of New Left journal The Universities and Left Review, become the the art director “who changed the face of Penguin Books in the 1960s.”

But the Partisan itself seemed to slip from the collective memory. Eclipsed by the other London that was just starting to arrive at that time.

“The Carnaby Street Mod scene was so vibrant and colourful that it’s bound to to displace this aspect of the history of the area,” says Berlin. “But I would also say that the loss of that memory is partially a result of the commercialisation of Soho; the loss of the small shops and the domination of big property interests. That’s always been happening of course, but it’s really taken off in the last 20 years.

“But, then again, if you read the history of Soho, people were complaining that it had lost its soul in the 1940s. So I guess there’s always churn in a city, it’s just a case which way the balance tips I guess.”

The Partisan Coffee House: Radical Soho and the New Left is at the Photographer’s Gallery until 25 September

You can read more about The Partisan in this London Review of Book article.

Fantastic piece of writing! Most enjoyable read so far of your subscriber only editions. Many thanks :)