How I survived the queer metropolis

Tales of teenage kicks and reflections on a revolution, by Stewart Who

Welcome to your free Monday edition of London in Bits.

This is a special, ‘guest contributor’ edition of LiB. All our contributors are paid (the base rate is £200) and we can only do that because of our paid subscribers

As a paid-subscriber you’ll have access to the back catalogue of paywalled articles (including last Wednesday’s guide to Londongrad) and you’ll receive three full issues every week. A subscription costs £5/month or £50/year, which works out at around 40p per issue. If you’ve been enjoying our newsletters then please consider subscribing so we can keep publishing the kind of independent journalism London deserves.

Don’t forget that you can follow LiB on Twitter and Instagram. And please feel free to share this issue on social media.

When we were thinking about asking someone to write about the evolution of London’s gay scene, our shortlist was one name long.

Stewart Who grew up queer in the sleepy enclaves of Surrey in the 80s, but once he escaped the suburbs he carved out an incredible CV for himself that includes stints as a performance artist, international DJ, club promoter, theatre director, podium dancer, model, film producer, psychiatric nurse… and hod carrier. Somehow he also found time to edit the gay weekly magazine QX for 10 years and provide the vocals for a Gold-selling house single.

In this essay marking the end of LGBT+ History Month, Stewart tracks the evolution of London’s gay scene through the AIDS crisis, Section 28, and the second Summer of Love. He remembers what it was like to navigate the streets of a pre-sanitised Soho and an ungentrified SW9, watch dawn break from the window of a night bus bound for Kingston, and score weed for his schoolmates in the fetish bars of Earls Court.

It’s a personal story of how the crucible of London was used to transform pain, ugliness and shame into glamour, beauty and pride and why now, more than ever, we shouldn’t take any of that for granted.

Unless you were also queer in the ‘80s, it’s hard to comprehend how difficult it was to simply exist during that era.

A homophobic climate poisoned British culture and haunted my teenage years. As the tabloids, establishment and the Thatcher Government were defiantly homophobic, this attitude prevailed in the playground. Kids can be cruel, teenagers are often brutal, and once Section 28 descended, the system itself offered no comfort to young people questioning their sexuality or seeking information.

I grew up in the suburbs of London, Kingston-Upon-Thames to be precise. Surrey was no place to be a queen, despite its history as a ‘royal’ borough. It’s fitting that this verdant county sounds like a middle class apology. If you were in any way ‘other’, the semi-detached, pseudo-purity of suburbia is nothing but a deceptive veil over latent violence, hostile blandness and cultural claustrophobia.

To reach my secondary comprehensive required two bus rides. Both were likely to deliver a double dose of bullying, before a day of random abuse at school. Then, there was the journey home.

Those bus trips were lawless, Lord of the Flies dips into pack mentality and a lesson in absorbing the cruelty of my peers and wider society. Bus conductors and random commuters looked the other way when gay kids got targeted and battered. Nobody fought your corner. Consequently, the biggest fight was with yourself.

The misery caused by this daily gauntlet is a memory that seems both alien and appalling in retrospect. No teenager should wake up and feel instant dread at the prospect of navigating life. I didn’t know for sure that I was gay, but the world told me in no uncertain terms, that merely appearing to be queer was a crime, and an invitation to vigilante justice.

Bringing potential promise to my adolescent life was the launch of Kingston’s Cinderella Rockerfella’s nightclub. It was 1985, and the arrival of this flashy riverside disco was an event of untold magnitude, much heralded by the Surrey Comet, our local newspaper.

It was discussed on street corners and in every playground in the Royal Borough. It felt to the fizzing cells in my teenage body that Kingston was to be blessed with a magical wand of glamour, decadence and escape. Yours truly was not going to miss out on that unlikely miracle.

How was it, once inside? LIKE A FUCKING DREAM. The incremental volume of the bassline as one ascended the stairs was an aperitif of adrenaline, before the explosive main meal of neon, mirror balls, chrome and geometrically patterned carpets.

A spell was cast that night, one which has proved alarmingly enduring. As I swept across the Saturday Night Fever-esque dancefloor, spiritually escaping the pain of being a teen queer in dreary suburbia, I decided that my future would be The Nightlife.

Within a year of that fateful night, I’d made steps towards becoming a DJ and over thirty-five years later, I’ve DJ’d everywhere from Ibiza to Latvia. I‘ve also worked as a podium dancer, club photographer, nightclub reviewer, door-whore and club promoter. That suburban disco punched above its weight, with an excellent alternative night called The Floorshow that was filled with goths and post-punk freaks. Wednesday night was Boilerhouse, a rare-groove proto-rave event that ran party boats from outside the club to Embankment and back.

Until The Marchioness tragedy in ’89, where 51 revellers died, floating river-raves were all the rage. They represented the aspirational end of pop-up events that defined the emergence of acid house. Less glam, but equally reflective of the era were the warehouse parties in Slough, shindigs in pub function rooms and the M25 events, fuelled by pager number mystery tours and car convoys.

Bouncing about, wide-eyed and wired with my straight mates was stupidly good fun, but despite the pilled-up hugging and smiley faces, it didn’t feel safe to be openly gay. In 1986, the nation witnessed ‘The Monolith’ advert on television (below). It showed the grim creation of a giant tombstone and featured the slogan, ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’. Fair play to Norman Fowler for a bold public health campaign, but it was a terrifying time to be alive and queer.

The ’88 Second Summer of Love was also The Autumn of HIV/AIDS and the Dawn of Section 28. The tabloids stirred up vicious hysteria and, at the age of 18, while other teens were having the time of their lives, this gay raver was nihilistic, self-loathing and resigned to a short, tortured life and a slow ugly death. It’s no wonder I sought escape in Ecstasy and Ralphi Rosario’s ‘You Used to Hold Me’.

London was a different city in the 1980s. It was seedier, definitely more dangerous, but also less corporate. The city’s undeveloped corners and abandoned districts were a magnet for both crime and creative, underground ventures. Before it went beige, Soho had edge. I once saw four sex workers take off their heels and batter a man in broad daylight. It was a savage gore fest, and maybe he deserved it, but his unfortunate blood splashed on my white jeans. It took weeks to wash out, and suddenly, Lady Macbeth made sense.

I witnessed this bloody episode while stood in the doorway of The Piano Bar, next door to Madame Jo Jo’s. Even in the 1980s, The Piano Bar felt like a portal to the ‘60s. It was popular with male sex workers known as ‘Dilly Boys, day-drunks, junkies, leery old men and off-duty drag queens. This volatile mix of misfits boozed and bruised each other, while an old queen played show tunes on a piano.

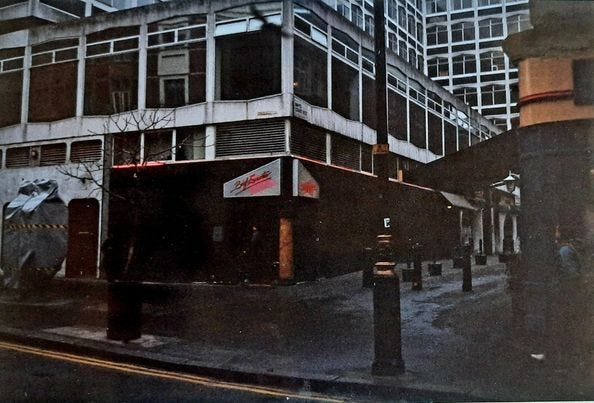

My first encounter with the world of gay leather and fetish, was at the smoky circus of S&M known as The Colherne in Earl’s Court. Located at 261 Old Brompton Road, the legendary pub for ‘clones’ had been a queer boozer since the ‘50s. It’s now a straight, gastropub called The Pembroke.

The Colherne’s blacked out windows and depraved reputation sat at odds with a starry, chatty and often theatrical clientele that included Freddie Mercury, Kenny Everett, Rudolf Nureyev, Ian McKellen and Derek Jarman.

The muir caps, chains and buckles may have scared a wary and ignorant public, but once inside, The Colherne was a friendly boozer with a campy bonhomie. In the late ‘80s, it was my ‘local’. Not ‘cause it offered a whirl of perversion, but because they happily served ‘snakebite and black’ and you could buy hash there on a weekday afternoon. While studying for A-Levels, I’d score at The Colherne for middle class college friends, impressed at my lowlife connections. Tarquin and Aubrey were unaware they were getting stoned, thanks to a gay biker in The Colherne known as ‘Judy’.

Back then, from my perspective, the leather scene was the epitome of naff. Today’s hipsters have reclaimed ‘taches and porno styling with gusto, but in the late ‘80s, it was style suicide. I’d rock up to The Colherne as a rampant raver, in purple Kickers, tie-dye t-shirt and baggy, pin-stripe denim dungarees. Sadly, that was the fashion at the time.

Acid house was sweeping parts of the nation, and the Earl’s Court gays were trussed up in chaps, and listening to Euro hi-NRG. Those older queens were baffled by my psychedelic threads and in return, their Village People vibes drew little but withering pity from yours truly. Who knew I’d live to see that style become de rigeur? East London straight boys in 2022 look like Earl’s Court gays did in 1987 - just with a little less leather.

In 1989, aged 19, I visited a man in hospital who was dying of AIDS. We weren’t close, but his family had abandoned him and he was set to die alone. This was a common occurrence at the time. The lack of compassion for people with AIDS will always be a greater ‘sin’ than the genetic lottery of being born gay. Seeing that skeletal soul, hollowed by disease was a deeply upsetting experience. It was a window onto body horror, shame and fear; but to be honest, my motivation in comforting him wasn’t entirely altruistic.

I knew that this man’s experience could soon be my own, that my friends and lovers may be dying on AIDS wards in years to come. I held his hand with sincerity and care, but a pragmatic part of me viewed that visit as a dress rehearsal for a future horror show, starring a cast close to my heart. Those were dark thoughts for a teenager, but they were dark times, and my pessimistic visions were entirely correct.

In 1989 the Age of Consent was 21 for homosexuals. Aged 19, my 22 year old boyfriend could have faced 14 years in prison for child abuse. It was lowered to 18 in the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, and finally lowered to 16 in England, Wales and Scotland in the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 2000. This ridiculous situation made it unwise or criminal to ‘come out’ and the police were a force to fear because of it. Reporting homophobic crime was more likely to provoke mockery or incarceration rather than sympathy or justice.

My coping strategy was to party like there was no tomorrow. Why worry about a future when death loomed large and life seemed fragile and devoid of justice? Passing my A Levels was a minor miracle, because most of the time I was on the lash in Soho. My partner in crime was a fellow student called Stuart Bird (The Third), one of 3 Stuarts in my Filofax at that time. We’d skip classes and spend the afternoon running between The Brief Encounter on St Martin’s Lane and Compton’s on Old Compton St.

The Brief was later transformed into exclusive member’s club, Bungalow 8, a glittering wing of the St. Martin’s Lane Hotel, but in the late ‘80s, it was a dark, sleazy gay bar, full of lonely old men happy to buy drinks for a pair of gobby students. We caused chaos, dragging the day into night and partying at Jungle on Monday, or Propaganda on Thursdays, both at Busby’s on Charing Cross Road. On Wednesday nights, we’d trip up to Pyramid at Heaven, an experimental queer rave night, hosted by Laurence Malice and boasting acid house sets from Mark Moore of S-Express.

Shoom, Land of Oz, Spectrum and Trip get much credit for fuelling the UK rave scene, but the gays were ahead of the game on that front. The queer roots of acid-house get forgotten in the historic wide-boy pipeline from Ibiza to London’s West End.

The Daisy Chain (1987-1990) at The Fridge in Brixton was incredible. Almost 2,000 people partying on a Tuesday night? Princess Julia, Jeffery Hinton and Mark Lawrence were the DJs and it was a hedonistic, loved-up bash that pioneered the new Chicago house sounds and brought camp warehouse vibes to the not-yet gentrified SW9.

It took two night buses to get from Brixton to Kingston and then I’d have a 30 minute walk. It was worth it, and the pills were strong back then. I’d still be buzzing as the N14 pulled into Kingston Bus Garage at dawn, nodding my head to Mr Fingers’ ‘Can You Feel It?’ on my Sony Walkman.

Despite the wide-eyed LOLs, people were dying. AIDS was the shadow that stalked the creative brilliance of London’s scene. Lesbians were nursing gay friends, because as a community we had to come together. We were under siege, from a disease that was terrifying and a society that thought we deserved to die.

There was so much shame, and people often vanished, to avoid looking ill in public. So many of my beautiful and spirited disco friends became worries, then memories. They’d be out every night of the week; preening, gurning and laughing… then gone. It wasn’t wise to ask questions, as people would be evasive, or worse, tell the truth.

“That one died, dear,” they’d whisper, sucking on a Marlboro Light. “Such a shame. His family were vile. They banned gays from the funeral. You didn’t sleep with him did you?”

Antiretroviral combination therapy changed the HIV/AIDS landscape in the late ‘90s. The fatalities slowed down and eventually became uncommon. It should be noted though, that in developing countries where medication is scarce, AIDS can still be a killer. PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) is a game-changing medication for people at risk for HIV to take to prevent getting HIV. These are amazing scientific evolutions that make many lives easier, healthier and longer. Quite frankly, it’s astounding I’ve lived to see such changes.

On early Pride marches, the Met lined streets to ‘police’ us. They weren’t on our side, and their feelings towards my community were clear. Today, the Met have a float and dance to Dua Lipa in their uniforms. The optics are queerly dazzling but if recent WhatsApp groups are anything to go by, it seems the boys in blue are still men to be feared. Cressida Dick’s appointment, like coppers in hot-pants, looked good on paper, but as we have learned, it means little on the ground and that’s where it matters.

I’m lucky to have survived, but many did not. Sometimes they haunt me. At a World AIDS Day event a few years ago, I spoke about the grief of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Afterwards, a young, gay man in his 20s harangued me for “talking about dead boyfriends and bringing everyone down”.

“The world’s moved on, mate,” he added. “Nobody’s interested”.

Perhaps he’s right, and that’s a perk of being young and having less to fight for. He almost had a fight on his hands that night. Thankfully, we were pulled apart as I screamed, “IT’S WORLD AIDS DAY WHAT DO YOU WANT ME TO TALK ABOUT?!”

It took a lot of work, pain and activism to achieve what we have in 2022. It appears the current Government would roll back our rights if it could. In lieu of law change they whip up a ‘culture war’ with the help of the media and a nation on its last nerve. We are furious, outraged and distracted, and yes, I speak for myself, but you can feel it on the streets.

Teachers are warned of showing ‘bias’ while talking about Stonewall, BLM or British history. A ‘war on woke’ seeks to create a climate of fear and a mockery of basic human rights. The BBC is under threat and tiptoes ‘round the Government, like a granny trying not to wake an angry baby. After the BBC quit Stonewall’s Diversity Champions Programme, director of news Fran Unsworth reportedly told the corporation’s LGBT+ network to “get used” to hearing opinions they do not agree with.

“You’ll hear things you don’t personally like and see things you don’t like – that’s what the BBC is, and you have to get used to that,” Unsworth allegedly said at the meeting. Thanks for the heads up, Fran.

Trans people are currently on the frontline of a culture war that’s entirely manufactured and disproportionate. It also has real life consequences. There’s a wholesale poisoning of discourse that feels very familiar to this old queer.

Boris Johnson has appointed six Tory donors to positions of power in cultural institutions since entering Downing Street. After coughing up £3m between them, these Tory cash cows are now on the boards of the National Gallery, Portrait Gallery, Tate and British Museum. This quiet infiltration came after an appeal to party backers to ‘rebalance representation’ on public bodies. It sounds to my careworn ear like ‘kick out lefties and undo diversity’.

It’s easier to be queer today, than it was a few decades ago, but those rights were hard won. There are people who feel they lost something in that battle and they’re kicking back with chilling efficiency. This is no time to be divided or complacent. We need to be alert and informed, not just about our recent past, but what might be an unpleasant future, if we allow it to happen.

You can find Stewart on Instagram and Twitter. His personal website is here.

News bits

Sadiq Khan has responded to the government’s ‘levelling up’ plan to divert investment from London “to areas that have been historically underserved,” (essentially cutting arts funding here by over £70 million ). In the mayor’s words the plan would “not only deliver a devastating blow to our city’s creative sector, but also damage the UK’s recovery from this pandemic”.

The government has come under more pressure to strengthen measures against “key figures” in London “who have amassed huge fortunes under Putin’s regime.”

The Royal Opera House has cancelled a summer season of the Bolshoi Ballet, which it said had been in the final stages of planning.

We’re not exactly sure why, but the South China Morning Post has a pretty in-depth look at the trend for “millennials moving into co-living creative hubs in London” (they look in particular at Greenwich Peninsula and Canary Wharf).

Talking of Canary Wharf, full planning permission has been given for three new towers on the Isle of Dogs, one of which is a Blade Runner-esque “51-storey build-to-rent tower with a red-metal mesh façade that curves around the building’s undulating footprint.”v

The Independent has been to visit Fine Liquids in Fulham, the shop that “stocks hundreds of bottles of natural water, costing up to £120 per bottle.”

Someone submitted a Freedom of Information request to find out how far some stolen Boris Bikes have travelled. Turns out, pretty far.

Great article. Just to ask: Is that really a photo of the Coleherne?