In today’s edition of London in Bits, editor Rob Hinchcliffe writes about the recent return of the ‘hypertext novel’ 253, and how this early example of networked fiction not only helped him get to grips with London, but also showed him the Web’s potential to bring people together.

This issue is public so, if you enjoy it, then please feel free to share it or post on social media:

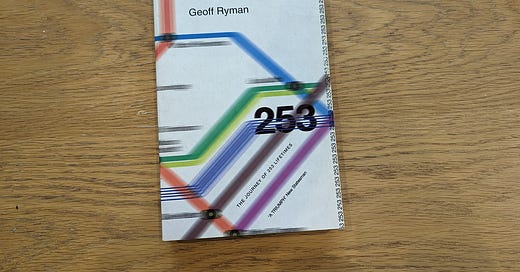

I first encountered Geoff Ryman’s novel 253 in its hardcopy form.

The ‘print remix’ of 253 was published in 1998, shortly after I moved to London and I read it straight away because I was hungry for anything which might give me some kind of insight into the city. I wanted something - other than the A-Z - that would make me feel more connected and less adrift in this unfamiliar landscape of ‘zones’ and ‘lines’ (and it didn’t’ hurt that one of the characters in the book worked on the same street I did).

Another reason I sought out the book was because, even though broadsheet reviewers had been a little bit sniffy about the novel, the internet seemed to love 253. While I was busy finding my way around this new city, I was also stumbling around the nascent ‘blogosphere’ (the term “weblog” having been coined just a year earlier), and I’d become increasingly impressed and influenced by what these pioneering LiveJournal reviewers had to say.

So, imagine how embarrassed I was to discover that 253 had existed in a completely different format, two whole years before I came across it.

In 1996, Ryman had taken his story of 253 people (252 Tube passengers and their driver) making the seven-and-a-half-minute journey from Embankment to Elephant & Castle, and published it as a series of linked pages, each one telling the story of a different character in exactly 253 words.

27 years ago he did this! Plus, even more amazingly, he’d managed to turn the website into a book; one that you could buy in an actual shop.

I loved the print incarnation of 253, but I soon realised that the online version was even better. What had been rendered as a boring old index in the book, became shocking blue hyperlinks online; and, to me, hyperlinks were the things that made the Web feel boundlessly connected and ripe with potential.

As well as using links as navigation (‘next passenger’) or highlighting how one person might be connected to another, Ryman also linked seemingly random words like ‘art’, ‘dyslexic’ and ‘minicab1’ - adding a whole other layer of serendipity and multiplicity to the experience of reading his story.

To jump from the mind of an “old-fashioned East Ender” in their mid-fifties, straight into the head of a young “clandestine author of slash fiction” just by clicking on the words ‘Star Trek’ was like finding some new form of magical realism, (come to think of it, it was probably the first time I’d heard the phrase ‘slash fiction’ too). And that slightly giddy, unmoored feeling that developed after clicking through these narratives would follow me out into the real world, making me hyperaware of the inner worlds lurking behind the sea of faces around me.

As Ryman himself said in a 1997 interview, in the digital version of 253 “the links change the meaning of the novel… [it] is about what makes people the same… It’s about the subliminal ways we’re linked and alike.” While, the print version was inevitably read “passenger by passenger,” turning it into a story about “how different we all are.”

While I enjoyed the story telling of 253, it was the html-facilitated sense of connection and kinship that I fell in love with. This early example of a well-executed piece of ‘networked art’ not only made my new home city feel less intimidating and labyrinthine, it also seemed to point towards all the ways that the native language of the Web could be used to bring people together in new, exciting ways…

… Of course, it didn’t quite work out like that. But that’s a different article for another time (although I don’t think it’s a coincidence that, shortly after discovering 253, I started a communal blog that would go on to become Londonist).

At some point in the noughties, the online version of 253 vanished. According to Ryman, he gave some “well-meaning convention organisers access to the site” and then, shortly after, realised his work had been wiped from the face of the Web.

Then, earlier this month, 253 was suddenly restored to the internet, resplendent in its mid-90s tones of indigo and purple.

If you’ve never read 253 before then you could do worse than spend a few hours clicking through its cast of characters (and the pigeon). It may be primitive in its presentation, but it has aged remarkably well, and it’s easy to see why it remains the touchstone for ‘interactive fiction’, inevitably referenced every time Netflix throw millions of dollars at a new slice of ‘immersive television’.

What Ryman created with 253 is a purely human story. By stripping his narrative down to its purest, most personal elements he managed to make the whole much greater than the sum of its parts. At the same time, he subverted the cliche of the cynical, unfriendly and anonymous city, and brought London to life in a way that hadn’t been done before (and has rarely been achieved since).

And he did all that without leaving the confines of a single Tube train.

Coming up on Wednesday 🎥

Owen Vince of the Awful Screen newsletter takes over our regular Electric Theatre column to write about a film from 1990, made by a Finnish director, that takes the viewer “on a joyride through London’s denuded fringes and hollowed-out centres”.

Subscribe to LiB today to make sure you don’t miss out:

5 little bits

After the horrendous accident at Cambridge Circus on Friday, the second ‘telescopic urinal’ just down the road on Villiers Street, has been shut by Westminster City Council “as a precaution”.

Harrods was cordoned off on Saturday evening after a 29-year-old man was attacked and taken to hospital with “stab or slash wounds”. No one has been arrested yet, but unconfirmed reports say that the attack happened after an argument over a watch in the Louis Vuitton section.

The neighbours of the MSG Sphere that’s currently being built in Las Vegas, are warning the residents of Stratford that its “one million light emitting diodes” are like “a sun on Earth”. (When people who live in Las Vegas say “actually, that’s a bit much,” then you should probably listen to them).

The Metro has always been a thinly disguised Daily Mail, and now that disguise is about to get even thinner. Thanks to the continuing lack of commuters and the rising price of newsprint, the paper “continues to run at a financial loss that is in no way sustainable,” which means that the editor of the print edition is “stepping down… amid a major print shake-up expected to lead to a number of redundancies”. As a result, no “dedicated content” will be produced for the Metro, instead all the stories will now come from the website or from the Mail or the i, and the Metro app will make “better use of technology and automation” (whatever that means).

Spike Lee is receiving a BFI Fellowship, which will be presented to him at the BFI Southbank on 13 February, when there’ll also be an “in-depth on stage Q&A” with the director and a screening of Summer of Sam. Tickets for the event go on sale today.

Showing incredible prescience, one of Ryman’s characters has developed an automated system for taxis that would make ‘The Knowledge’ redundant.